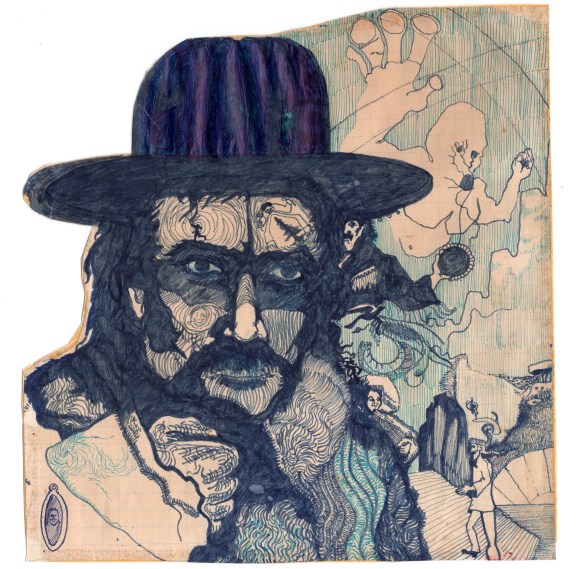

A picture drawn in 1968 of my older brother Jerry, which also reflects how I saw myself, especially after our dreams for the “Summer of Love” began to crumble and fall apart.

In June of 1968 I graduated from high school in Fort Worth, Texas. I stood in the driveway of my family’s house on Danciger Street and bade my father “farewell,” hardly listening to his plea for me to take care of myself. I was heading to San Francisco, along with a couple of friends. I knew my older brother, Jerry, was already there, in the Haight-Ashbury district, and I and my friends couldn’t wait to leave our conventional families and neighborhood behind, and join in the “Summer of Love.” Indeed, I thought (very clearly in my own mind) that I would never return to my family again. I had had it with my parents, my grandparents, the whole scene of traditional religion, culture, and society. My friends and I would join the movement for free love, “make love not war,” “flower power.” We really believed that we might be able to usher in a new “age of Aquarius.” And so, we hit the road and drove to San Francisco. On the way, about the time we drove through Los Angeles, Robert Kennedy was killed there, following in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April, and Kennedy’s brother John five years earlier.

As soon as we arrived, we learned rather abruptly that the “District” itself was not entirely free from the world’s problems. We found Jerry and his friends in one of the row houses that we so-called “hippies” occupied for several square blocks around the cross streets of Haight and Ashbury. No one paid rent. No one minded who came and went. The owners and the police had given up trying to enforce normal property laws (just like in Seattle today). On our first evening in the house, we encountered a young black man knocking from outside on the second story window of our house. He was leaning out of the window of the next-door house (those houses were only a few feet apart in many places). We opened the window and he shuttled through, running for the front door, and yelling back over his shoulder as he went that he had just shot someone in the other house, having been caught trying to rob it. Not exactly the welcoming party to the summer of love that we had expected, but perhaps this was just an aberration.

No. The next morning we found that everything we had left in our car parked on the street had been stolen as well, including all of our camping gear and most of our clothing. No problem, this was the place of the New Age, the new world of love, and we were going to make it happen, even if it cost us a little bit here and there. Revolutions do require sacrifice.

I began to have deeper doubts about the depth and soundness of our vision when I sat down with Jerry the next day to talk about our plans: How we were going to change everything for the better in our world of civil rights marches, assassinations, and the Vietnam war. I was only 18 years old, and I hadn’t really been a very committed student of history, philosophy, economics (or anything else, to put it mildly); but even I knew that something was deeply wrong and askew when Jerry explained to me that the way we were going to correct the imbalances of our society was to “Walk into the banks. Rob them. And then just redistribute the money equally to everyone” (a kind of defund the police solution if ever there was one). I remember thinking, though I didn’t say it out loud at the time because Jerry was the closest thing to a “Messiah” that I had, “But, Jerry, what will happen then? How will people behave with all of that cash? Will we all just suddenly become good?” I didn’t ask, so he didn’t get a chance to answer. But, had I asked, I imagine he might have regarded me as rather naïve or uncool, perhaps in need of some more LSD or marijuana, which we were all using a lot.

Jerry’s next plan sounded better, but it ended in disaster. We would take a homemade “house-truck” that belonged to one of his friends and drive down to Mexico. We would purchase a boatload of marijuana, and then bring it back into the country, literally, by boat, landing somewhere in the Big Sur area. We would distribute the weed, make some money, and everyone could get high and celebrate with a great “love-in,” which meant of course lots of sex with whomever was willing. Things went south when we were stopped on Highway 1 for making an illegal U-turn, and then arrested for having drugs in our possession. We were put into the county jail in separate cells at San Luis Obispo County ( or, as the name was ironically abbreviated on the building and on the side of police cars, “SLO. CO. JAIL,” and “SLO. CO. POLICE”). We spent several days in jail before they decided to let us go. They were arresting hundreds of kids every day along the coast, and had nowhere to keep all of us. They let all of us out except Jerry.

I hadn’t known it, but Jerry had been arrested a few days earlier for possession of marijuana in San Francisco, and was due for a court appearance. In leaving for Mexico, he had jumped bail and skipped town, so now there was a warrant for his arrest. After our release, the rest of us hung around for a couple of days in San Luis Obispo, before heading back to San Francisco where Jerry had been extradited. Back in Haight-Ashbury, without my brother, no money, and a head full of broken dreams (my Forth Worth friends had long since gone home) I tried to fit into the scene as best I could. But the social scene in the district was pretty much like the social scene anywhere, and the ideals of even a few months earlier were falling into disarray. Everyone pretty much looked out for themselves, and indulged their own appetites. People were taking drugs and having sex with pretty much anyone. And I had not eaten for about three days.

I remember getting very angry about the way things had turned out. At one point, I lay on a bathroom floor, cursing the god in whom I said I did not believe, the god in whom, even then, I did not want to believe. ”Why, god, have you put me in this position? Why did you let me come to this?” And some how, in my own mind, the words came through to me, “Craig, I did not put you here. You did this.”

As I began to starve, I felt I had no choice. I called my father and asked for help, the prodigal who couldn’t even make his own way home. But unlike the biblical prodigal, I wasn’t really repentant yet, or able to register what a fool I had been with all of my pseudo-romantic self-imagery and grandiose ideals. Dad said he would come right away, and told me where he would meet me. So, Dad came to Haight-Ashbury. He got a hotel room. Got some food into me. And then he went to talk with the judge in the court where Jerry was being held.

The judge agreed to release Jerry if Dad would pay the bail and promise to take Jerry out of the state, a deal to which Jerry agreed. The next morning, when Dad went to collect Jerry from the house where he had gone for the night, he was gone. No one knew where. Dad didn’t see Jerry again for at least three years. But he took me back to Fort Worth, where I felt alienated from everyone and everything. I felt I didn’t know my parents anymore. I thought of suicide. All of my dreams and visions had been deconstructed, and what was underneath was really just a desire to appear heroic, to indulge my desires, and to live my life free from the constraint of what others might want or need. All of the veneer of my social visions and commitments had crumbled. My friends and I didn’t really know how to save ourselves, much less the rest of the world. But that didn’t stop me from trying to hold on to the old narrative.

Back in Fort Worth, I took up with my old friends. I knew there were huge gaps in our world view, but where else could I turn? My world had been deconstructed by the raw data of experience; and I didn’t want to admit it. But I began secretly to read and ponder some other things, things that wouldn’t make any sense to my friends who still believed in the summer of love, things like the Gospel of John, C.S. Lewis’s Problem of Pain, and George Herbert’s 17th century poetry. And little by little I began to review the history of my life and to see resonances that I hadn’t seen before. And I began to write songs. One of the first was a surprising reversal of my rejection of family, called “The Hills of Coleman County,” a song about my grandparents’ old place out in the country:

I can still remember, back in my childhood days,

living with Mama and Papa, and eating the country way. . . .

And I am heading for the meadow that lies beyond those hills.

I feel there’s something calling to me, and I’ve got to take my fill.

Also, one of George Herbert’s poems (discovered in freshman English at the University of Texas at Arlington where I went with my friends in the fall) struck me like a shaft of light with images of something very like what had happened to me on the bathroom floor back in Haight-Ashbury some months earlier. I took Herbert’s poem “The Collar,” revised it for contemporary lyrics, and turned it into a rock song that I called “The Table.” This was indeed so very much like me on the floor cursing God:

I hit the table, and shouted, “No more do I want to spend any time

On this blasted living.

Why should I sigh. My lines and life are free, free as the road, loose as the wind.

Sure there was corn before my tears did drown it out.

Sure there was wine before my sighs did find it out.”

But as I grew more fierce and wild with every word, I thought I heard a voice

Calling, “My Child.” “My Lord.”

In part two of this reflection, I will look further into how coming into contact with the Christian Gospel by various means affected my understanding of my time in San Francisco and the SLO. CO. JAIL.

Awesome Craig. Did not know of this history of you going to SF in ‘68 and that whole experience. You being 3 years older I thought you were way ahead of me in unmasking the false hopes and dreams of the 60’s & early 70’s. Dave Corcoran and I both were arrested for drug possession in ‘71. For pot. Enough to consider I was dealing and that NJ cop thought he just broke open the French Connection. This was the beginning of my journey to faith. From such delusion to Faith in Jesus in August ‘73.

Dan, Glad to remember with you how the Lord’s Spirit, and the Gospel about him, was working in both of our lives in those days to begin the long process of creating us anew. Still on that road, aren’t we? Yet also sure of where it is going because we can see it more clearly all the time in him. No doubt there will yet be many surprises for us on the way to the full inheritance. What eye has not seen, nor ear heard.

Yes. And amen. D

Amen. And amen.