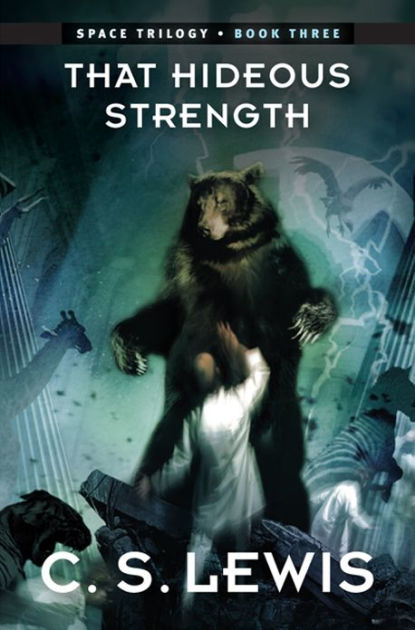

BANQUET AT BELBURY

Overview Question

In an odd sort of way, the overview question for this week provides an occasion to evoke two rather contradictory emotions: On the one hand, to breathe a sigh of relief (and hope, even joy) as we watch the terrible villainy of the NICE at Belbury at long last pay itself out in death and destruction; yet, on the other, to consider soberly (bravely and even sorrowfully) the hard result that this implies for those in our own time who have followed the worldview and the lifeworld of Belbury. These results, in other words, are both sad (Saturn) and hopeful (Jove).

What I suggest, then, as a way to take in and understand the chapter as a whole, is to follow the action of each Part and to ask at each stage a single Overview Question:

How do the actions and events of each Part demonstrate the logical results of following either the fallen eldil (as at Belbury) or the good eldil (as at St. Anne’s and in Merlin)?

This means that you will be looking as you follow the actions of Wither or Merlin, Frost or Fairy Hardcastle (and others) for signs either of the good eldil, or the fallen ones. Signs, that is, and for example, of the heavenly Mars (courage, patience, etc.) or the fallen shadow of Mars (domination, coercion, etc.). Or, for two very different examples, signs of the good Venus (kindness, life giving help) or the fallen Saturn (despair and indifference rather than “good grief”).

To do this, you will need to remember what we learned about the planets in the last chapter and in Chapter 12, where we also discussed the virtues and the passions that characterize the good angels (God’s messengers) and their fallen counterparts. And try to keep in mind how this is both a joyful and a sorrowful exercise because we are talking about a real world, our world, not just a fictional one.

DEEPER-DIVE QUESTIONS

1. How does the collapse of language (i.e., the power of Mercury) at the banquet—first with Jules, then with Wither and throughout the room—illustrate the logical consequences of the post-Enlightenment exaltation of the individual (i.e., individual freedom and “reason”) and the denial of the traditional understanding of God, truth, and reality? What signs can you discern today of this kind of collapse in the speeches and responses of our elected officials and other leaders of business, media, society and, yes, even the church?

2. Why does the dissolution of language and meaning at the banquet (and in society today) lead to the shadow side of Mars—that is, to mindless violence, bravado, and murderous coercion (rather than to courage, fortitude, and self-control, etc.). Which characters, in which parts of the chapter, clearly illustrate this dissolution of the true power of Mars? What actors illustrate fallen Mars today?

3. Which of the good eldil shine forth in the actions of Merlin when he frees both the animals and the human prisoners (including Mark and Mr. Maggs) and how is Merlin’s way of sending them forth also a recovery of the good order of creation (“nature” rightly understood as commanded by the Creator of all, Maleldil)? As a corollary to this question: Why does it make sense, from the standpoint of the traditional worldview, that the animals would attack the advocates of Belbury to destroy them? Is there some sense in which nature itself will ultimately “refuse” to support what is evil? How is “nature” reasserting itself today in rejection of woke anti-nature ideology?

4. In Parts 4, 5, and 6, Wither, Feverstone, and Frost, each in his own way, enacts the logical consequences of the worldview that they have all embraced and tried to live by (their modern lifeworld). How do the murderous actions of Wither, the self-absorbed and self-centered actions of Feverstone, and the suicidal actions of Frost, demonstrate the consuming passions of the dark eldil–that is the passions of fallen Mars, fallen Jove, and fallen Saturn, respectively? What actors and agencies in the spiritual battle of our cultural, political, and media wars today seem determined to embrace these same or similar passions represented by the fallen powers as they are also described in Scripture? (For Scriptural descriptions see, for example, Romans 1:18-32; Ephesians 4:17-6:20.)