As we prepare for the Christmas holidays during this Advent season, and some of us plan perhaps to take some time off from our regular schedule of life and work, are we also aware how our Lord’s incarnation has redefined the world in which we live and work?

The Apostle Paul addresses this question when he describes Jesus’s incarnation as the complete reversal of the fall of man in the Garden of Eden. When the Son of God came into the world, unlike our first parents, Adam and Eve, he “did not consider equality with God as something to be grasped, but he emptied himself and became a servant, and was born in human likeness” (Philippians 2:6-11). Likewise, later on in his ministry with his disciples, Jesus took a towel and a bowl of water and, in the manner of a common servant, he washed their feet, calling them to be servants as well (John 13:1-20).

And so, the incarnate Word came into the world to reverse the whole history of false pride, jealousy, envy, and vanity that ruled from Adam, to Cain and Abel, to Joseph and his brothers, right down to Jesus’s own disciples, who vied with each other for places of status and prestige, and also of course in our world today. “He was obedient even unto death on the cross,” Paul says, and so “God has exalted him and given him the name that is above every name . . . Lord.” The result is that our lives can be restored in him. Paul says simply, “Have this mind in you which was also in Christ Jesus.”

But what does it look like in practice when our lives are restored in the image and power of the Son of God? Surely part of the answer must be that there is no job too “small” or “menial” for us to do. In a world that is habitually conscious of status and rank, we are called to serve in any and every way that is needed. This has perhaps a special relevance during the holiday season, when it can be all too easy to leave some tasks to others. But Paul calls us “not to think more highly of ourselves than we ought to think,” and to bring our gifts (whatever they may be: shepherd or wise man, doctor or dishwasher) into the service of the Lord; and above all to “offer him our hearts,” as Christina Rosetti’s poem expresses it. These are themes that Paul went over again and again in nearly every one of his letters, suggesting just how important and challenging this kind of restoration can be (Romans 12:5-21; compare 1 Cor. 12; Eph. 4).

There is much, no doubt, that many of us are still learning about serving in this transforming way of humility as we seek to live truly in the power of the risen Christ and in the fruits of his Spirit. But there is a second, and perhaps even more difficult implication of the incarnation for our lives and work.

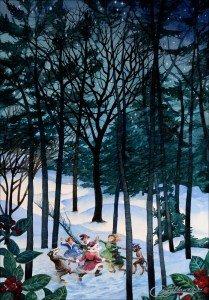

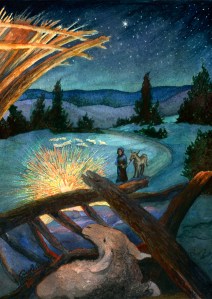

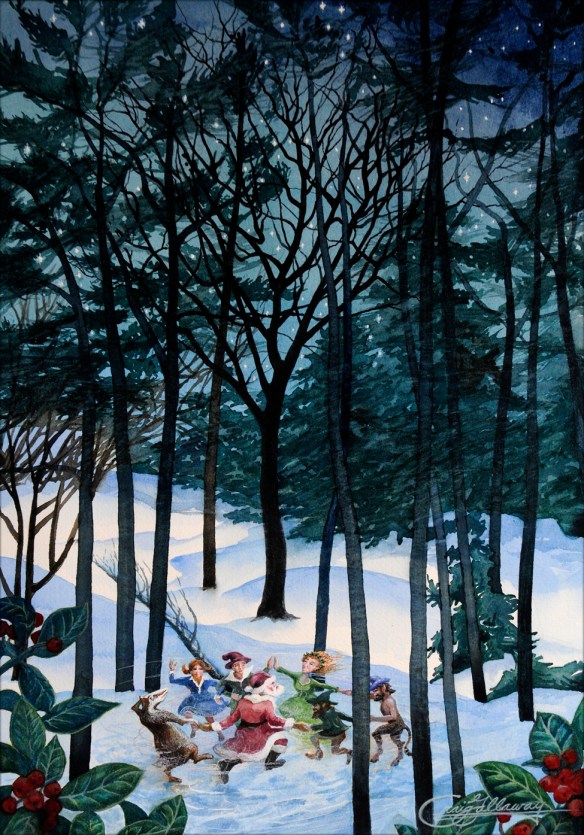

Snow Dance, watercolor by Craig Gallaway, copyright 2010. Based on C. S. Lewis’s Narnia Tales, The Silver Chair. The children were held captive in a cave below ground until they escaped into the open air to join the dance of creation with the other free peoples of Narnia.

Our Lord’s servant ministry also sets us free from the need to base our identities on what we do. Because we live our lives in him, we are not defined by which gifts we are given, or what job we have. Our work should never become an idol, vying to control our life when our true Lord would free us for the life of new creation. This is especially significant in this day and time. It is a “bleak midwinter” indeed, when companies in every sector of our economy are requiring their workers to embrace ideas and actions that do not honor the Lord of all creation. But being a servant does not mean agreeing to do whatever anyone asks us to do. We have only one Lord; and he is the one who sets the terms of our service (Romans 12:11).

I realize that I am raising what must be for some of us a very difficult set of problems. Deb and I understand this difficulty personally because, though we are retired now, we had to deal with this at one point in Craig’s career as the editorial director of a major religious publisher. But Paul seems to know and understand this territory as well. For, after describing the gifts in Romans 12:3-6, he goes on to describe in more detail how we are to use them. “Love must be genuine,” he says. “Hate what is evil; stick fast to what is good” (Romans 12:9). Perhaps some of us will have to sever ties with a particular job or company because they demand that we “conform to the pattern of this fallen world.” But Paul also says that we should do good to everyone, even to our enemies, because this sometimes has the effect of winning them over (Romans 12:10-18). Therefore, some of us may be able to stay at a compromised job because the Lord is using us to change things.

And then Paul goes on to call us to use the “ruling authorities” who are given by God to restrain evil (Romans 13:1-5). The court system in America today is often serving as a last bastion of protection for our freedom of religious and moral conscience under God. Above all, Paul keeps his own mind grounded in the presence of the risen Christ (who, he says, is even now “praying for us,” Romans 8:34), and in the power of the Spirit (who “intercedes” for us, 8:26), and on the goal of new creation itself. This is what gives him (and us) a calm confidence, no matter what difficulties arise, that nothing can separate us from the love of God in Jesus Christ (Romans 8:22-39).

And so, as strange as it might seem to a secular observer of “Xmas,” we celebrate Advent and Christmas by rejoicing in the freedom that our Lord brings into our lives to serve him openly, generously, and without pride, envy, or fear of losing our position in a dark and embattled world. For he has broken the power of those fears and passions, first in his own faithful life and death, and then in his resurrection and the sending of his Spirit to work powerfully among us.

Heaven could not hold him, while the earth was stained.

Heaven and earth will shine again, when he comes to reign.[1]

____________________________________________________

- Some readers may notice that Deb and I have changed the words to Christina Rosetti’s original second stanza. This is because the original words–“Heaven and earth will flee away when he comes to reign”–do not reflect the full scriptural promise of new creation. Was this a slip by Rosetti into the artistic idealism of the romantic movement of which she was part? Did she not realize that Jesus was born physically, and suffered physically, and was raised physically, in order to be the first born from the dead (Col. 1:18) and to restore the material world? Or was she referring only to the cleansing stage of judgement day, to which both Paul and Peter refer (1 Cor. 3:10-15; 2nd Peter 3:4-13).