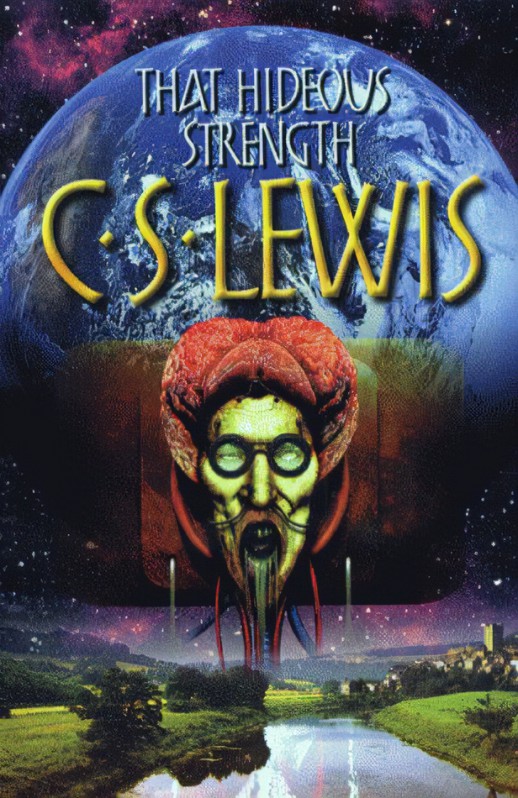

THE CONQUERED CITY

Overview Question

In this chapter, the efforts of NICE to take over and control the town of Edgestow and surrounding villages has reached a crescendo. The “stages of cultural revolution” (demoralization, destabilization, crisis, new normal) that we observed earlier in Mark Studdock as an individual (see Chapters 5 and 6) have now reached the level of “mass formation” for the people of Edgestow as a whole. And yet, due to the nature of these dynamics, not everyone is being affected or responding to the trouble in the same way or at the same time. This brings us to our Overview Question for this chapter:

What are the different ways that people at Edgestow are responding to the troubles stirred up by the NICE? What explanation can you give for these differences? Try to identify at least two different sub-groups. Also, what parallels for these differences can you identify in recent cultural and political events of American society?

As you ponder this question, you may find it useful to revisit our earlier discussion (in the general Introduction) of the “Stages of Cultural Revolution” as described by Yuri Bezmenov, and of “Mass Formation” as described by Mattias Desmet. Neither of these models is difficult to understand in itself; and both cast a good deal of light on the kinds of psychological and social dynamics that Lewis portrays among the people of Edgestow. Both also help clarify the cultural dynamics at work in society today.

DEEPER-DIVE QUESTIONS

1. In Part 1, the leaders at Belbury (Wither and Fairy Hardcastle) continue with their efforts to manipulate Mark so they can force him to bring Jane to Belbury. They seem confident that they can pull this off, given their view of Mark’s nature, by framing him for the murder of Prof. Hingest. At times they seem to be succeeding. And yet, as we work through the chapter as a whole, we find Mark at other times responding in ways they do not predict. Indeed, by the end of the Part 3, he almost responds to Dimble’s offer to help him leave the NICE; but then he settles back again into his double-minded ways. What account would you give of this inner conflict in Mark so unforeseen by the NICE?

2. In Part 2, Mark makes his second attempt (this time successful) to escape from Belbury. He goes to Edgestow to look for Jane; but first he encounters a continuous flow of refugees leaving their homes under Emergency Regulations. In a local pub he overhears other residents (not yet displaced) discussing how the refugees must have brought this on themselves. He goes home and finds Jane gone but an envelope addressed to Mrs. Dimble. By the end of this part, despite having just run away from Belbury, Mark is thinking of himself as a victim of the Dimble’s interference, and of how nice it is (all things considered) to be part of NICE. What kinds of resources or practices, and what view of the world would Mark and the people of Edgestow need in order to avoid being sucked into this powerful mass formation?

3. In Part 3, Mark has gone to Northumberland College to confront Dr. Dimble about the whereabouts of Jane. But here, Mark meets someone for the first time who is clearly not under the influence of the NICE; and, indeed, Dimble stands in direct and forceful opposition to everything that the NICE represents. Lewis leaves several clues in this part and at the beginning of Part 4, as to the sources of Dr. Dimble’s strengths and virtues in this regard. Why and how is Dimble able to stand for what is good and true despite Mark’s adoption of the “victim” and “shaming” mentality. What practices and sources can you identify that help Dimble take this stand, even though he clearly struggles at times?

4. In Part 4, back at St. Anne’s, and based on Jane’s dreams, Ransom is putting together a team to go out and look for Merlin, though no one can yet be sure which side Merlin will take. One thing is clear, however, those who go must be in a relationship of obedience to Maledil. On this basis, Jane can go; and MacPhee cannot. Why does MacPhee’s lack of obedience leave him less suited than Jane to face the unknown forces of spiritual warfare? What strengths or virtues are enhanced simply by placing oneself under the obedience?

5. Extra Credit: In Part 4, Ransom talks about Merlin, Logres, and the “parachronic” (alongside time) state, a state where time is suspended in some way that allows the influence of ancient figures upon current life. Can you think of anything in the sphere of human experience today where something like this influence of character and principle across time really does take place? (This question is a first stab at an important issue that we will come back to in later chapters.)