A picture drawn in 1968 of my older brother Jerry, which also reflects how I saw myself, especially after our dreams for the “Summer of Love” began to crumble and fall apart.

By the end of my first year at the University of Texas at Arlington (June 1969) the pain of staying the same had become greater than the pain of making some kind of change. Not only had I returned the previous summer from the debacle of Haight-Ashbury. I had now lived and partied with my friends on campus for a year. My girlfriend had become pregnant and had an abortion. I had played in a rock band, demonstrated with SDS, been arrested and put in jail with the band in Sherman,Texas for helping stage a curfew demonstration against the Sherman police. And I was aware that my personal life was a wreck, and my political ideals, though grand in scale (“Make love, not war!”) were also historically vague and practically incoherent.

When summer came, I moved home to live again with my parents. I had not reconciled myself to their culture or religious ideas; but I knew I needed something more stable and more self-disciplined in my life.[i] I was still going out with my campus friends, partying at local lakes and rivers, and trying to live it up. Yet I was also dissatisfied with this scene. I knew it was empty of something more substantial that I was longing for. An early sign of this shift in perspective came when I resigned my summer job at a local music store where my friends often hung out, and took a job as a garbage man with the city of Fort Worth. I could make about twice as much per hour. Dad said to me, “Well, at least you can say that you started right at the bottom.”

I also began at this time to read more regularly in the New Testament, especially the stories in the four Gospels about Jesus: what he did, whom he met, and how he interacted with a wide variety of people. I would be out with my friends until late at night; then come home, fall into bed, and open my Bible to read until I fell asleep. I saw how Jesus interacted with a full range of everyday ordinary sinners: an adulterous woman, a greedy tax collector, power-hungry men like the Chief Priest and Pilate, and with his own failing followers (like Peter) who had wanted (like me and my friends) to be known for their revolutionary style and bravado, only to run away in confusion and bewilderment when their ideals proved groundless and self-indulgent.

As I read the gospel stories, I knew they were also about me; and given the ending of the Gospels, where the risen Jesus promises to continue to be present with his followers by the presence and power of his Spirit, I took a second step. Lying alone in my bed in the wee hours, after earlier efforts to live it up with the gang, I began to pray. The prayer was very simple, somewhat in the vein that my father later told me had also been one of his early prayers, “Lord, if you are there, can you also help me?” And the wonder of the thing was this: He was there. “Yes, I will help you. Trust me, Lean on me” (Matthew 11:28). The responding message came through very clear in my mind and heart. And, for the first time in a long time, I rested.

Thus began a couple of years of rather bumpy beginnings. Bumpy, yes, but not all that uncommon I think for a young believer, even in its bumpiness. A sort of two steps forward, one step back; start, stop, and start again, journey. One big step forward came as I found that my experiences of faith were inspiring me to write my own songs and music. Until then I had played mainly cover songs with the band (Cream, Dylan, etc.). Now I was writing about something that was rising up in my own life. Yet even now, my songs sometimes expressed a kind of ambivalence about leaving my old way of life and actually identifying myself as a Christian. One song in particular, the “Washday Blues,” expressed this ambivalence, drawing for its imagery on then popular TV ads about laundry soap. The song is addressed to Jesus, though he is never named explicitly. (You can hear an old recording of the song here.)

WASHDAY BLUES

I’ve been wondering, just what to do about You.

And you know, my mind needs laundering

Cause all I’ve got is dirty confusion.

And I’ve been looking for a brand-new recipe;

But I can’t seem to get nothing cooking:

Baked, broiled, fried, stewed, or fricasseed.

And you know, I need some real good enzymes to brighten up my day.

But it can’t be just any old detergent.

I need something strong to wash my dirt away.

I’ve got a ring around my collar, and a spot on my tie.

I’ve got the washday blues; I feel like I could cry.

If something doesn’t happen soon, I may lay down and die.

What can change my scene? Is it Mr. Clean?

O, I’ve been wondering just what to do about You.

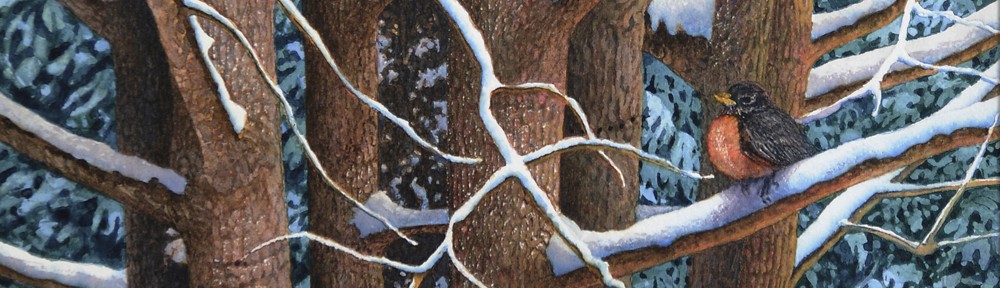

Glen Cove, watercolor by Craig Gallaway, copyright 1970. Based on a stock photograph and my own memories of my grandparents’ West Texas farm. I was trying to recall the atmosphere of their life and faith.

By the end of my second year at UTA (1970), still living at home with my parents, and hanging out with my rambling friends, the tension inherent in my double life was beginning to wear thin. Trying to live both as a cool neo-pagan rocker, and as a Christian (at least in private) has its fault lines and tremors. I had by then written a number of songs. I was surprised in a way to find myself in some of these songs (and in some of my paintings for watercolor class at UTA) reaffirming the bonds of faith and country life that tied me to my family (for example, “The Hills of Coleman County”, mentioned at the end of Part 1). And though this kind of song resonated to some extent with a new turn in rock and roll at that time toward a more progressive country style (Dylan, the Birds, the Band), and wasn’t therefore a direct challenge to my revolutionary “style,” I think I knew at some level that this affirmation of family history was turning my political ideals toward something much more down to earth and grounded. I was letting go the world of sweeping claims about social justice and rediscovering the world of struggle, pain, and even joy in common life. This came out more explicitly in a Christmas song I wrote at the end of 1969, entitled “White Star.” (You can hear an early recording here.)

WHITE STAR

White star, how You came to be

shining down upon that country place

is beside me.

Bright and Morning Star, how you came to be

Walking around inside that country man

Is beside me.

And I was so surprised to find

That anything as ordinary as that country place

Could lighten every space

And brighten every face.

Bright and Morning Star, how you came to be

Looking right into these country eyes

Is beside me.

You’re inside me.

The tension inherent in my double life came to a head in the summer of 1970 when my father suggested that I might help out a young local preacher/evangelist named Billy Hanks. Billy was working with several young gospel singers, such as Cynthia Clawson, and he needed a guitarist for studio recording. I had a new red Guild guitar and I went straight to work. As a result, I myself became involved in some of Billy’s crusades, sharing my songs and my embryonic witness all over Texas, and eventually with the Youth for Christ organization in Europe. I also met a new set of friends and musicians; and this led later to my working with a popular Christian rock group called Love Song, as an opening act for concerts at various Texas colleges and universities.

Meanwhile, some of my old campus friends were wondering what was happening with my “music career.” I think some of them liked the music I was writing, and at least some of the lyrics. The band members even helped me, with various instruments, to produce some early recordings of the songs. But others in the troupe took offense at my increasingly public faith. The fellow on whose reel-to-reel tape machine we recorded even charged me with wanting to steal his tapes in order to get a music contract, get rich, and leave him out of the windfall. I had no such plans, and never pursued his vision for me; but I knew I had to walk away from that kind of suspicion and hatred. So, I did.

Another song that I wrote at about this time coincided with the decision to break more clearly from my old pattern. I was aware that my friends and I, with all of our ideals about social change and freedom and “love,” had long been disgruntled with life itself, working jobs that we didn’t really like or want, waiting for the weekend to come so we could party, get high, and escape our boredom, only to find ourselves worn out and starting another week in the same sort of stupor as the week before. I knew I needed to turn a corner, to spend my time differently. And what good did it do to keep sharing my songs when, as far as I could see, I might only be bugging them with my “witness”? I needed to strengthen what few real gains I had made (personal and spiritual) and begin with more effort to “redeem the time,” (Ephesians 5:16). The song I wrote about all of this was entitled “Time.” It was addressed in this case both to myself and to my old friends. It was a kind of farewell song and a wake-up call to make good use of time–and everything else we were being given. (You can hear an early recording of the song here.)

TIME

What can we do to save time that we think we can use

For a better time as soon as we have finished

What we’ve got to?

And what can we do to pass time when we find we’ve saved too much

And we’re spending all our time

Wondering just how we can pass it?

What does time mean to you?

Does it mean just that another day is through?

Are you rushing? Are you wishing? Are you lazy?

Do your days just pass you by, come and go?

Do you know the reason why?

I was letting go of one way of life. I was taking up another. In 1971, I began working as a youth director at the First Methodist Church in Carrollton, Texas, with pastor Ken Carter and his wife Freddie. I learned a lot at Carrollton about keeping a schedule and connecting with people who had regular jobs and families, people who were willing to work with me as we tried to make a difference in our surrounding community. In the summer of 1972, for example, instead of spending a lot of money, as we had done the year before, for the youth group to travel to Kentucky to work with the great Appalachian Service Project, we found a way to create our own service project in the rural countryside around Carrollton. Like ASP, we helped local people and families living in poverty to rebuild porches and roofs, and we enjoyed musical and cultural exchanges with the generous black congregations whose members welcomed us into their communities.

At the same time, among the people I had met through Billy Hanks, were two twin brothers, Brad and Stan Ferguson, who were part of the Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship at North Texas State University in Denton. I lived with Brad and Stan on the NTSU campus for one semester in the fall of 1970, and then later spent time with them while I was completing my art degree at UTA. Among other things, my friendship with Brad and Stan helped me to clarify what it would mean to make a more grounded break from my old life of so-called “free love,” and to move into a new way of life in Christ that looked instead for a kind of wholeness, justice, joy, and wholesomeness in faithful marriage.

This was not a simple or easy time of transition for me. I was a young man in art school, taking life-drawing classes with nude models. I wrestled quite a bit with the meaning of my own desires. I even started at one stage in my art work, without really knowing the background or history, to drift toward the ancient gnostic heresy which once dogged the early Christians. This is the idea that the solution to our passions and unruly desires is in some way to get rid of the body itself, to be taken away to another world where there will be no body to bother with. I memorialized this in an etching that shows a young man, divided severally in his own mind, somehow breaking away from his brain and the world in order to find peace.

One day in Denton, when I was showing Brad some of my life drawings of nudes, I became embarrassed and said something about how he didn’t have to look at all of this “nasty” stuff. And Brad simply reminded me that for us as Christians, the body is not “nasty.” It is God’s good creation. Our task is not to escape it; but to learn to live faithfully with it and in it, in the physical world, with self-control, holiness, joy, and wisdom. Here, in a deeper connection, I was learning ever more clearly how the personal and the political, the social and the moral, far from being separate compartments, really belong together; and how practical and down to earth this way of Christian faith is designed to be. The Spirit was working with me, even as I at first misinterpreted what I thought the Spirit was aiming at. But this is how the Spirit often seems to work when one is in need of deconstruction and reconstruction!

In the summer of 1973, after graduating from UTA, I returned to the San Francisco area to live in Richmond and to work with a group known as “The Christian World Liberation Front.” Led by Jack Sparks on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley, CWLF sounded like another radical political group. And in a way it was. But it was focused on helping young people recover a sense of faith, hope, and grounding in Christ. I too was still learning how to bring my old revolutionary ideals down to earth, to embrace a way of life that was faithful in love, disciplined in work, focused on service, and open to all people under the guidance of the risen Lord and his Spirit. I came to see that these practical steps of faith, as common and ordinary as they seem, really are the Christian alternative to the overblown rhetoric that we often encounter in revolutionary circles, such as the Zealots in the New Testament, the hippies of the 1960s, and the recent cultural harangues from the riots of 2020. This is also, by the way, the kind of mission grounded in faith and individual responsibility that we find at work today among leading black Christians and public intellectuals such as Robert Woodson, Shelby, Steele, and Glen Loury.

So this is how I began to learn over time what it meant to sing the words of my own song: “Jesus’ blood, dripping on the stones, has set me free to soar.” Set free not only from the physical confines of the SLO. CO. JAIL, but also from the spiritual and moral rabbit trails of my own limited vision, my story, my self-understanding. His death and resurrection, his defeat of the powers of sin and death, and his continuing power and presence by the Spirit, are the foundation for a real revolution that aims finally at resurrection and new creation. Nonetheless, like the Apostle Paul, those of us who follow him do not dare nor even wish to claim that we have already arrived, for we are still on the road hiking with purpose toward the final restoration and victory (Philippians 3:12-15). But we are “in him” and that makes all the difference: On the road of new creation, fighting back against the fallen powers, under the banner of the King!

[i] I wish I could say that I recognized clearly during the early years portrayed in this account just how much my father and my mother had been an ever-present help to me. After all, when Dad came to Haight-Ashbury to get Jerry and me out of trouble, he was, in a way, enacting the gospel in person. I didn’t see it so clearly then. Later, looking back, I was able to recognize how, to put it mildly, it had not been easy for him to come to that particular “far country” to find us, to bear the costs (monetary, personal, and emotional) and the drab ignominy of our sins and failures, and all of this in order to give us a second chance to start again; yet to see no immediate signs of gratitude or change in either of us. Dad was no more perfect than the Apostle Paul. But, like Paul, on behalf of the runaway slave, Onesimus, and like King Jesus who is the source and foundation of this whole endeavor, he was ready to take our debts upon himself in order to bring about, if possible, the desired reconciliation.