“Real Life Is Meeting”

Overview Question

In this chapter, both Jane and Mark move further along the path of what can only be called, in Christian terms, “conversion.” They have come a long way since the beginning of the story. They are both being converted from their earlier formation in the Enlightenment worldview, during their college and professional years; and they are being converted to what we have called (from the beginning of our study) the traditional worldview. The latter also includes what we came in the last chapter to identify with the role of Merlin in Lewis’s story: Merlin the advocate of God’s order of creation in nature, and of Christian marriage, and of English common law with its conservation of basic human rights and freedoms (the 7th law) as these are shaped by biblical faith. All of these are integral parts of the traditional worldview (lifeworld) as it came to expression in England from the Middle Ages onward until it was challenged head-on in the 17th and 18th centuries by the anti-tradition and anti-religious worldview of the Enlightenment.

Jane and Mark are being converted from their former college training and formation; and both are coming to see and appreciate why the traditional worldview (with its inherent lifeworld) holds much that they now want to re-embrace if they can only discover how. But each of them comes to this by a different set of means or mediations. This brings us to our Overview Question for this chapter:

Look carefully at Mark’s “conversion” in Parts 1 and 4 (note Lewis’s use of the term) from Prof. Frost’s deconstruction of all traditional values, and toward what Mark only knows to call the “Normal.” Then, look closely also at Jane’s struggle (in Parts 2 and 5) first with Mother Dimble’s traditional ways about marriage, and then with her own licentious fantasies, until she turns in the garden (after her talk with Ransom) toward the “presence” of God. Based on your observations, try to identify the means by which each of them is helped along this path of conversion. What kinds of things are involved in each of their cases (e.g., mentors, memories, conscience, innate or instinctual longings or repulsions, Scripture, and other traditional echoes). By what means from within the traditional worldview are Jane and Mark drawn into the orbit of God’s further influence and healing?

DEEPER-DIVE QUESTIONS

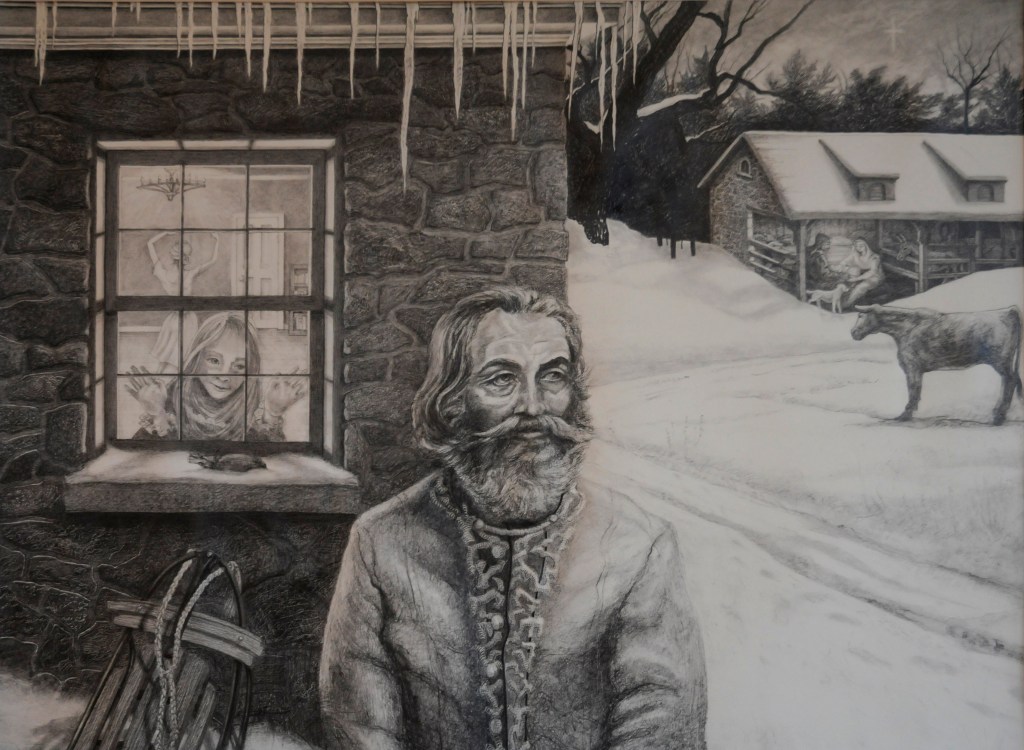

1. The title of this chapter may hold a clue to the importance of several “minor” characters at this point in the story, characters whose impact we might be inclined to ignore unless we understand the deeper significance of the conversion that is taking place in both Jane and Mark. For example, in Parts 1 and 4, Mark is introduced to the Tramp—Frost’s and Wither’s false Merlin—whom they hope will help them advance their plans to combine ancient magic with modern technocratic controls. During Mark’s sentry duty, however, he finds that he is able to bond with the Tramp in a way that is more grounded in common humanity than he had ever achieved in his efforts to join the inner ring of power with Frost and Wither. Similarly, Jane is at first put off by Mother Dimble and Ivy Maggs because they represent a kind of storied traditional role for women and marriage to which Jane has been averse; but then she begins to discover that they are part of something that is much deeper and truer to real life than her habitual feminist ideas have led her to believe. Why is it that these “common people,” with their uneducated and even uncouth ways (the Tramp), embody the promise of meeting real life in a deeper and truer way? What is the source of this real life that Jane and Mark are meeting in these common people?

2. In the middle of the chapter, Part 3, we find a brief digression on the fate of Mr. Bultitude, the bear. Lewis goes to some lengths (as he always does in his descriptions of the bear) to notice how Mr. Bultitude’s way of processing information is not the same as that of a human being. Mr. Bultitude does things by instinct, not by moral choice, reflective deliberation, or conscience. This echoes Lewis’s traditional sense of the hierarchy among animals, humans, and angels (an echo of his love for the “triadic” thinking of the Middle Ages[i]). The result of this triadic thinking is to highlight, by contrast and comparison, the specifically human task of being human. How do the innate limitations of Mr. Bultitude’s instinctual behaviors help to clarify the specifically self-reflective and moral nature of the choices and loyalties that are now required of Mark and Jane if they are to complete their conversions and become fully “human” in the traditional sense?

3. All along the way in our study of THS, since we began early last August, we have tried to evaluate the relevance of Lewis’s insights regarding the cultural battles of his time (the mid-1940s) with the cultural and political battles of our own. With only three chapters after this one left to consider, this may be a good time to take an interim inventory. Here are some of the major discoveries that we have made along the way so far. Consider briefly how each one of these may find a counterpart in the events and agencies of our own day.

a. In Chapter 2, the faculty and Feverstone discuss how their ideology will spread through all the institutions of society—including education, politics, science, business, the press, etc. (cf., the neo-Marxist Long March Through the Institutions). Where is this sort of thing taking place today?

b. Also in Chapter 2, we saw how Busby and Mark and others endorse a kind of “applied science” which is really a mask for their social ideology and a way to gain control both of society and academia, for example, by rejecting traditional scientists such as William Hingest (who still require empirical evidence to support their claims). Where have we seen this sort of thing today?

c. In Chapter 6, Mark caves in to the NICE and assumes the role of an “activist journalist,” writing propaganda articles that whitewash the NICE for public consumption. What are the primary arms of activist journalism today, and on what stories have they practiced this kind of white washing? Are there any news agencies today that practice traditional journalism?

d. In Chapter 7, Jane discovers that she has held a view of marriage and sexuality that is centered, like her Enlightenment worldview, on the freedom of the individual self (self-expression, self-definition, self-indulgence). This has led her to regret her marriage to Mark, and to be vulnerable to adulterous thoughts. Where do we see this self-centered view of sexuality and even of marriage in our culture today?

e. In Chapter 8, Filostroto proclaims to Mark his vision for a future technocratic society where people are programmed by technology, and where human beings achieve a kind of immortality through artificial intelligence. Where do we see this kind of ideology at work today?

f. In Chapter 10, the NICE take control of Edgestow as the four stages of cultural revolution come full circle with the declaration of emergency powers. At the same time, normal people become jaded against their fellow citizens in a kind of mass formation which allows them to “stay under the radar,” protect themselves and their own jobs, while they “go along in order to get along.” Where have we seen this sort of thing at work today?

g. In Chapter 11, Jane goes with other members of the St. Anne’s community to look for Merlin, and they all find themselves shaken awake by the nominal degree of their own faith when they have to face some kind of real spiritual power or danger. Where have we seen, in recent events, the awakening of faith as a result of coming face to face with the denial of human rights and basic freedoms, including the freedom of religion and conscience under God?

h. In Chapter 13, Ransom explains to Merlin why God will only work to set things right by working through human beings who are willing to be his partners in the work of restoration (the 7th law). Where in our political debates today do we find this concern to preserve the role of human conscience and agency under God? And where do we find this calling either manipulated (made to serve a prior state agenda), rejected, or simply absent from the discussion of how to restore and renew society?

[i] C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image (Cambridge, 1964) pp. 56-57, 71-72.