Some might think it odd for Deb and me to choose an old Bob Dylan song, about the challenges of getting married, to celebrate the birth of our Lord and his purpose to restore the good order of creation. But then, in the Bible, there are few things that need restoration more than God’s good gifts of marriage and sexuality. And there is something in the very structure of Dylan’s song that echoes what the Bible has to say about this—how our incarnate Lord, born at Bethlehem to be both King and Bridegroom, wants to restore the order of marriage in his kingdom. [i]

We learn from the Apostle Paul and others that Jesus is the true bridegroom of his people, the church, and that he has suffered much to make the church his bride (Ephesians5:21-32). The epistle to the Hebrews tells us that, “He was tempted in every way as we are, yet without sin,” and this is why “he is able to sympathize with our weaknesses.” (Hebrews 4:15). Paul tells us that he was “obedient even unto death on a cross . . . and so God has highly exalted him and given him the name that is above every other name, Lord” (Philippians 2:8-11). And Hebrews again speaks of how “He endured the cross for the joy set before him, and then sat down by the throne of God,” (Hebrews 12:2) from whence he now reigns, “until God has put everything in order under his authority” (1 Corinthians 15:20-28).

This is the basic biblical narrative of the incarnate Son of God, from the time of his birth, through his faithful life and death, his resurrection and sending of his Spirit, and on now with his people, the church, toward the time when the great restoration will be fulfilled. And this is the narrative of our lives as well, if we have joined our lives to the living reality of his, by faith. For we are called to live our lives in him, and this means to follow him in the way of faithfulness and, yes, in the way of sacrifice. Paul puts it like this in Ephesians 5.

“Husbands love your wives, as Christ loved the church, and gave himself for it . . . so that it might be holy and without blame” (verses 25-27). “Wives, be subject to your own husbands as to the Lord” (verse 22).

In this way, Paul calls wives to exemplify what every Christian, including husbands and the unmarried, are called to do (cf., Romans 12:1-2). And he calls husbands to imitate the faithfulness of Christ, so that they may encourage and strengthen their wives in the pattern of life (in Christo) to which all people are called, again including the unmarried. We are all called to imitate the greatest Bridegroom of all, in the power of his Spirit, so that our lives may become whole and strong in him.

Of course, there are ramifications that ring out into our lives from this narrative. For example, we must not make an idol of sex–that is, to give it more power in our lives than it is due–unless we want to become confused about its real purpose. The degradations that result from idolatry are what Paul has in mind in Romans 1:18ff. Also, we should recognize that marriage has several purposes—mutual help, comfort, the procreation of life, and the preservation of chastity (Genesis 1-2, 1 Corinthians 7)—not all of which are focused on sex. If we are to follow our Lord, and live in his Spirit, we must be ready to take up the larger and wider callings that come with being good wives and husbands, as well as good neighbors and members of his bride, the church. Whether in our own personal lives, or in our corporate life together as his people, eros must be governed by agape. [ii]

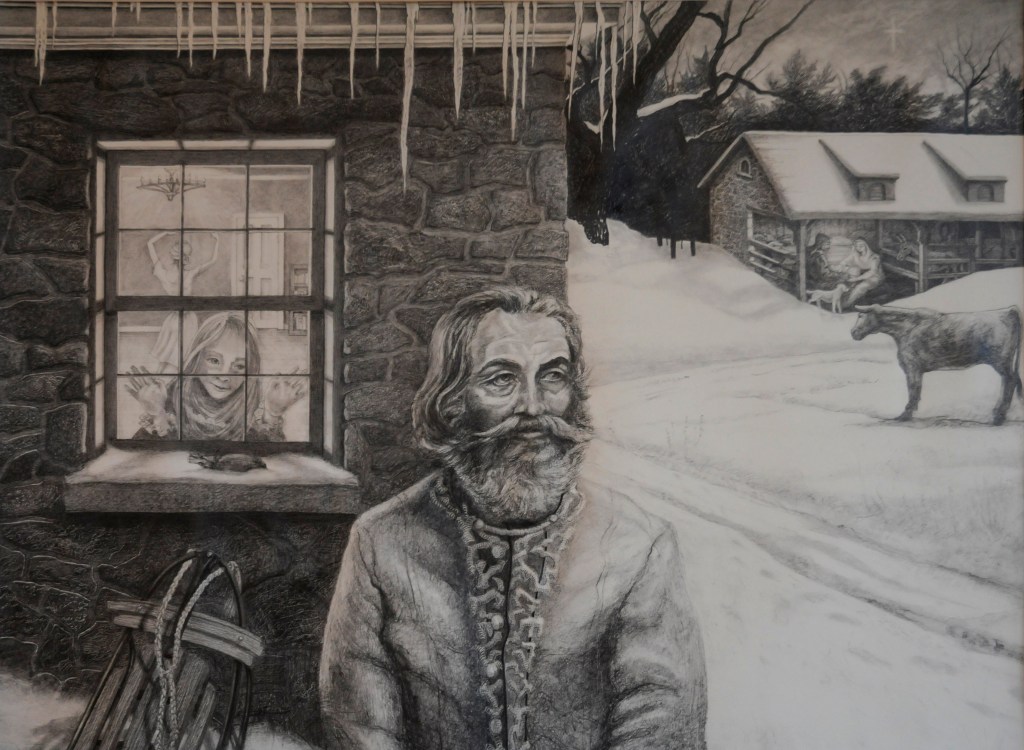

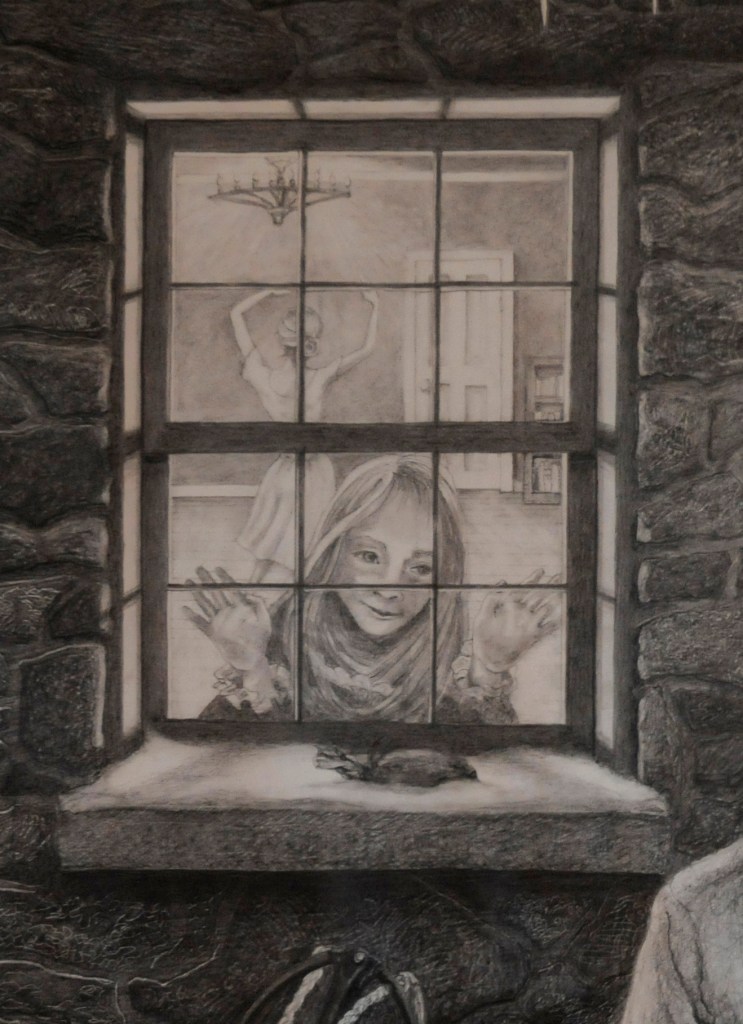

But what, then, does all of this have to do with an old Bob Dylan song about a prospective bridegroom who is struggling to manage his inner fears, temptations, and doubts as he anticipates the arrival of his wedding day? Will he bolt and run, for fear of failure in the challenges of married life ahead? Or will he “get his mind off of wintertime” and rejoice in the arrival of his bride? Will he listen to the siren voices of romantic wanderlust, and travel to some distant place, or will he “pick up his money and pack up his tent” and look forward to the coming of his bride? What did Jesus do? What is he doing now?

By the third verse of Dylan’s song, we discover what our protagonist has decided to do. He will stay and embrace the covenant of marriage, with all that it entails. He plants his feet on solid ground and calls for the instruments of creativity and provision (perhaps also of procreativity): “Buy me a flute and a gun that shoots, I won’t accept no substitutes.” He intends now to honor his bride, like the Bridegroom is doing. He will fight for her against the enemy’s opposing forces, even if some of his own troops are weary or lagging. [iii] And he will “climb that hill no matter how steep,” so that he may rejoice in the joy set before him.

Thus, with the scriptural narrative ringing in our ears, we know what our Lord, our Bridegroom, has done (in his faithful life, death, and resurrection) and is doing (in the presence and power of his Spirit) in anticipation of the great day when his faithfulness will be fulfilled, when we too shall rise like him from the dead, and there shall be a new heaven and a new earth, and there shall also be a great wedding banquet for the Lamb and for us.

Can you hear, as Deb and I do, his voice echoing beyond our own as we sing about the place of our marriage in his New Creation purpose and care?

Ooo wee, ride me high, tomorrow’s the day my bride will arrive.

O Lord, are we gonna fly, down in that easy chair.

[i] Deb and I aren’t saying that Dylan intended or foresaw all of the biblical allusions that we see reflected in his imagery. But he did become a Christian later in life; and he was always deeply influenced by the Bible, as he once told Paul Stookey.

[ii] This seems to be the main point of C. S. Lewis’s reflections in The Screwtape Letters, regarding the demonic strategy that uses certain art forms to confuse people about the importance of “being in love,” that is of romantic or erotic passion, as if this were the foundation and purpose of marriage. If the demons win this battle, says Lewis, they also create an excuse for divorce when the level of excitement changes over time. But then, Lewis also portrays, in That Hideous Strength, how the affection of eros can be restored where husband and wife learn to embrace the larger pattern of servant love (agape) and obedience to God. Eros can return as a result of a more caring and wholesome way of life together, not as the goal or purpose of marriage itself.

[iii] Given the culture wars in America today, many of which turn on the definition of sex, gender, and marriage; and given the strong rhetoric of “hate speech” that has been cast against Christians for trying to uphold, much less to recommend the covenant of marriage as a source for sexual healing in our culture; Paul’s discussion of spiritual warfare (Ephesians 6) just after his instructions regarding marriage (Ephesians 5) does not seem at all accidental. In any event, to promote the Christian practice of marriage in our present culture will be a spiritual battle, to be sure; but one that the church must accept with a whole heart.