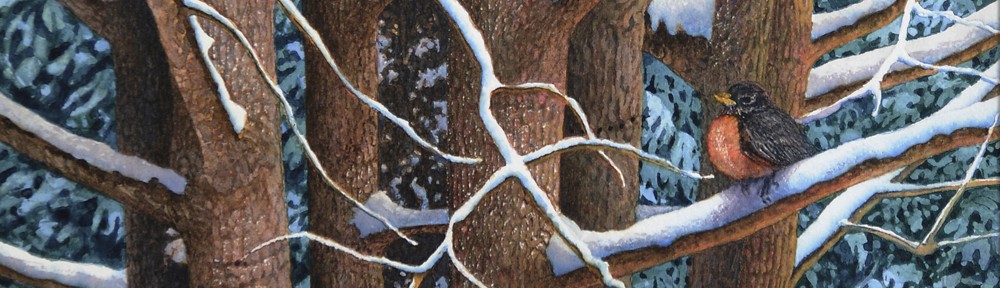

Hello Sparrow, pen and ink drawing, copyright 1973 by Craig Gallaway. The presence of a bird sitting and singing peacefully just beyond the bathroom screen once put me in mind of the biblical promise of new creation, when “the lion shall lie down with the lamb and a little child shall lead them” (Isaiah 11:6).

When Jesus rose from the dead on the first Easter morning, he became what Paul would later call him, the “Firstborn from the realms of the dead” (Colossians 1:18). Thus, Jesus was for Paul the beginning, the source, and the pattern for the restoration of the whole world, human beings included, according to the Creator’s original and ultimate intention for creation. This vision of creation restored is at the very heart of Paul’s theology as shown throughout his letters, and especially in several climactic passages such as Romans 8:18-39 and 1 Corinthians 15:20-28. It is echoed as well in the final visions of John’s Revelation, (chapters 21-22).

The big picture, according to Paul, is that something has happened in the death and resurrection of Jesus that comprises a complete reset for fallen human beings in our role as stewards and keepers of God’s good creation. Moreover, the restoration is ongoing for those who live in Jesus’s Spirit, and it will not be complete until the Day of the Lord when all things are finally and fully restored (1 Corinthians 15:20-28). So, right now, “the whole creation waits in eager expectation for the sons and daughters of God to be revealed,” and to take back up the role that we lost under idolatry and sin (Romans 1:14-32; and 8:19-21).

What is more, this restoration of creation that has begun first in Jesus himself—his faithful life, his death, and his resurrection—is now going forward among those who put their faith in Him and are, thereby, led, guided, corrected, strengthened, and restored by his Spirit in the pattern of his life, death, and resurrection. But what does this pattern look like in terms of public life and behavior? Can we really speak of something like the “politics of Jesus,” the “politics of the new creation?”

I believe we can. But if we want to be true to Paul, perhaps we should begin with an important distinction between things that are essential to this political vision of new creation in Christ, and things that are not essential. Other terms for the non-essential side of this contrast include: things indifferent, and the Greek term, adiaphora. Paul uses the latter term in Romans 14:1, where he begins a longer discussion about disputable “cultural” matters such as what one should eat or drink, or which special religious rules and holidays one should observe. His primary point is to steer the Christians at Rome away from the temptation to make a federal case out of every type of issue. Not all issues are absolute. And when we are dealing with non-absolutes, Paul says, we should practice charity; that is, we should be willing to let go of our own preferences in order to support, protect, or appreciate the consciences or sensibilities of others (Romans 14:1-6).

John Wesley, in the eighteenth century, summed up Paul’s concern in terms of a threefold principle:

“In essentials unity. In nonessentials, liberty. In all things, charity.”

A simple ecclesial example of what it means to defer to others regarding something non-essential is C.S. Lewis’s memory of the value to his soul of joining in the hymn singing of his little Anglican congregation at Oxford, even though his own more highbrow tastes were sometimes offended in the process. This may sound petty until it is one’s own musical tastes that have to be set aside. Another example might be the decision to forego a “harmless” glass of wine if one’s alcoholic friend could be tempted as a result to “fall off the wagon.” There are many such examples, where the Lord’s Spirit of love could lead us to give up our own “rights” or preferences in order to help, appreciate, or take care of others. Indeed, it is not hard to imagine situations in our schools and communities where the political decisions we face offer no single best solution for all parties, but only trade-offs between different agendas and priorities. In such situations, it is important that we remain open, flexible, and neighborly toward different opinions and possibilities.

At the same time, the principle of adiaphora does not mean that all of our behaviors and decisions are indifferent, or disputable. This is certainly true for Jesus’s followers. It is also true for other groups who self-define their priorities in the culture wars of our time, such as Antifa and Black Lives Matter, though their list of “essentials” is in many cases diametrically opposed to the politics of Jesus.

It should be noted right away that Paul keeps his list of essentials relatively short. He is interested in life in the Spirit of Christ, not in creating a continuously expanding list of rules for behavior. Nevertheless, Paul does not fail to identify areas where Jesus’ followers are called to a specific way of life in his Spirit that is absolutely non-negotiable. We will look here at three of these: 1.) Unity in Christ which moves beyond all ethnic identity groups or divisions, 2.) Holiness in personal life that focuses especially on marriage and sexual self-control and rejects the pan-sexual self-invention of pagan or neo-pagan culture, and 3.) The servant goal of work in Christ that springs from the motive of service rather than status or entitlement. These three essentials in the politics of Jesus, moreover, clearly address several contested issues of racism, justice, and economics which preoccupy our current political debate. Let us look briefly at each in turn.

Unity in Christ beyond Ethnic Divisiveness: In his letters to various churches (Galatians, Corinthians, Romans) Paul often addresses claims of favoritism, superiority, or abuse between different ethnic groups. The primary tension he faced arose between those of his own Jewish background who believed that their identity as God’s people conferred a special status, superior to all of the other ethnic groups of the ancient world—Gentiles, barbarians, Scythians, Greeks, Romans, etc. Though he had himself once been a zealous Jewish Pharisee (Saul of Tarsus), who sought above all to priviledge his own people, and probably hoped at one time to see them freed from Roman domination through violent revolution, Paul the Christian had come to see, after his encounter with the risen Jesus, that, as he put it in Galatians 3:28, “In Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek; neither slave nor free, neither male nor female; for you are all one in King Jesus.”

For Paul, this unity of all ethnic groups in Christ was an essential. One could not compromise this unity and remain a member in good standing of Christ’s people, the church. When Jews came from Jerusalem to insist that the Galatian Gentile Christians must be circumcised according to strict Pharisaic custom, Paul insisted that to submit to this demand would make the death and resurrection of Jesus of no value (Galatians 2:21). Indeed, what Jesus accomplished in his death and resurrection was to fulfill the ancient promise to Abraham that God would bless all nations (ethne) through Abraham’s seed. He would bless, that is, not just the Jews but the whole world. And Jesus was the fulfillment of this promise. For he was the “seed” of Abraham, along with the people of every ethnic background who put their trust in Him (Galatians 3:16, 29).

We see a very similar set of ethnic tensions playing out in the culture wars of our own time. On one side, we find groups like Black Lives Matter insisting that since whites have been priviledged in the past, African Americans must be priviledged now. In other words, one of Black Lives Matter’s essential principles is the notion that blacks and whites must be kept in adversarial conflict in order to achieve the BLM conception of justice. On the other side, we find a large and growing group of leading black Christians and public intellectuals who argue that the Black Lives Matter strategy is a sad diversion from the real problems that trouble the black community and other struggling groups. Leaders such as Robert Woodson, Shelby Steele, Glen Loury, Carol Swain, and others, take a more Pauline and Christ-centered approach to this debate and argue that what is needed in the black community is a recovery of individual self-discipline and responsibility grounded in the renewal of the black family, educational choice, leadership training, and in the community of faith. This kind of renewal, furthermore, according to Shelby Steele, will focus on the individual as an American citizen, not as a black, or brown, or white person who belongs to a separate identity group. The contrast could not be clearer. (See Shelby Steele, Race in America, Virtual Policy Briefing, the Hoover Institute.)

Here, then, are two pictures in high contrast to each other of our political and racial future as a country. One is a picture of the unity of all ethnic groups as citizens of one country, working together with common tools for common goals. This is a picture that is commensurate with the politics of Jesus and the new creation. The other is a picture that promotes and prolongs ancient divisions between ethnic groups, pitting identity groups against each other as a strategy for correcting the past. Such demands for diversity have a long history already of producing division rather than unity. This vision is not consistent with the politics of Jesus. A similar set of contrasts emerges when we look at matters of marriage, sexual ethics, and the role of the family in relation to recent political debates.

Holiness in Marriage beyond Pan-sexual Self-invention: As mentioned before, Paul did not make a long casuistic list of behavioral practices that are essential for the political life of Jesus’ followers in the new creation. But holiness in sexual practice and marriage is one of the essentials about which he was very clear. He writes again and again in his letters of the necessity of turning from the old fallen pattern of sexual license, self-indulgence, and promiscuity in the surrounding pagan culture (1 Corinthians 6:9-11; Ephesians 5:1-10) and of channeling the God-given desire for sexual union into the central Christian praxis of marriage (Ephesians 5:21-33). Indeed, when this praxis is idly ignored at Corinth, he insists that the community there must discipline a wayward brother in no uncertain terms if they are to maintain their identity as a community in Christ (1 Corinthians 5:1-5). Furthermore, as his extended discussion in Ephesians 5 and 6 suggests, Paul’s long-range concern is not just about sex per se. It is about the fully human and healthy formation in Christ of husbands and wives along with their children and other members of the household. And all of this relates, finally, to the restoration of the Creator’s original intention for human beings (Genesis 1:28; 2:24; Ephesians 5:31). To be “in Christ,” the first born from the dead, and to celebrate life and faith in Christian marriage (whether one is married or not), is to be on the way to the new creation.

Someone might think that marriage and sexual ethics are a rather tangential topic if our focus is on solutions for political, economic, and racial issues. It is remarkable, however, that some of the primary voices in the current debate take positions precisely on this topic. In the Black Lives Matter mission statement, for example, there is a clear rejection of the biblical essential for holiness in marriage and sexuality as an obstacle to the kind of social changes that BLM seeks. According to the statement, BLM seeks to disrupt what they call (oddly, given its sources in the Middle-East) the “Western-prescribed nuclear family structure . . . by supporting each other as extended families and ‘villages’ that collectively care for one another, especially our children . . ..” Also, the statement goes on to affirm “the intention of freeing ourselves from the tight grip of heteronormative thinking” in order to foster “a queer-affirming network.” By contrast, according to Shelby Steele and others in the 1776 Unites project of the Robert Woodson Center, the recovery of the black family, with a mother and a father in the home raising children, is an essential key to the economic and political recovery of the black community. Indeed, according to Steele, if the black community does not address this issue of individual character formation within the black family, then there really is no hope for a broader political or economic recovery. (Shelby Steele, Race in America)

Unity in Christ across ethnic lines that would otherwise divide, and holiness in marriage against sexual self-indulgence and self-invention: To these two essentials in the politics of Jesus and the new creation can be added a third.

Work as Service Rather Than Status: What motivates us in the work we do? Paul clearly encountered a lot of status seeking among the early Christian communities with whom he worked. Jesus himself was tempted by vanity just before he began his public ministry (Matthew 4:1-11; especially 6-7). Over against this status-seeking or vanity, Paul regularly raised up a picture of the Body of Christ, given a variety of gifts, all of which are given for one purpose, “to serve others” (1 Corinthians 12-13). In Romans 12:3-8, after calling Christians to offer their whole lives to God as a living sacrifice, he advises them not to “think of yourselves more highly than you ought to think,” but rather to think soberly, in line with the special gifts that God has given to each one. If the gift is giving, he says, then give generously; if it is kindness, do so cheerfully. And all of this aims in the end toward a great and final goal in the new creation, to be fully formed as those who love as God loves (1 Corinthians 13:1-13).

Loving service is the ultimate goal and motive for the Christian life in the new creation, of which Jesus is the first-born from among the dead. But how does this play out in the political ideas that are shaping our current debate? Perhaps the best place to address this topic is with the strategy of the Woodson Center to foster “Community Enterprise Centers” and “Violence Free Zones.” In various parts of their print, video, and audio resources, members of the Woodson Center staff, including Robert Woodson himself, speak of how they work with youth in troubled neighborhoods to build self-esteem and a sense of dignity and leadership that comes from helping others; and of how this has led to the transformation of neighborhoods once oppressed by gang violence into “Violence Free Zones.” The emphasis in these programs is upon Christlike service and self-discipline that transforms individuals from the inside out. By contrast, what we see and hear from the Black Lives Matter groups are threats of violence, riots, and unlawful mayhem (“No justice, no peace!”) unless they are given what they demand, whether this be reparations, defunding of the police, or other collective and monetary demands.

Again, the contrast between the politics of Jesus and the new creation, and the politics of groups who seek a solution through government programs and collective threats, could not be clearer. On one side is a clear set of three essentials for those who embrace the Christian way toward political health and healing: ethnic unity, the family, and work as service. On the other side, in direct opposition, are three contrary essentials aiming at a very different outcome: identity politics, pan-sexual anti-family ethics, reparations and entitlement. One may choose between these optional visions. One cannot combine them. The essentials on either side are not so superficial as that. They drive all the way down to bedrock in both social praxis and in the human heart. Even so, it is important in concluding these brief remarks to frame the essentials of the politics of Jesus as what they indeed are: partially realized goals toward which the Christian community is called and committed to work. The essentials of the Christian vision are grounded in the ongoing work of God’s Spirit to bring his Kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. Still, the work we do now is not in vain (1 Corinthians 15:58).