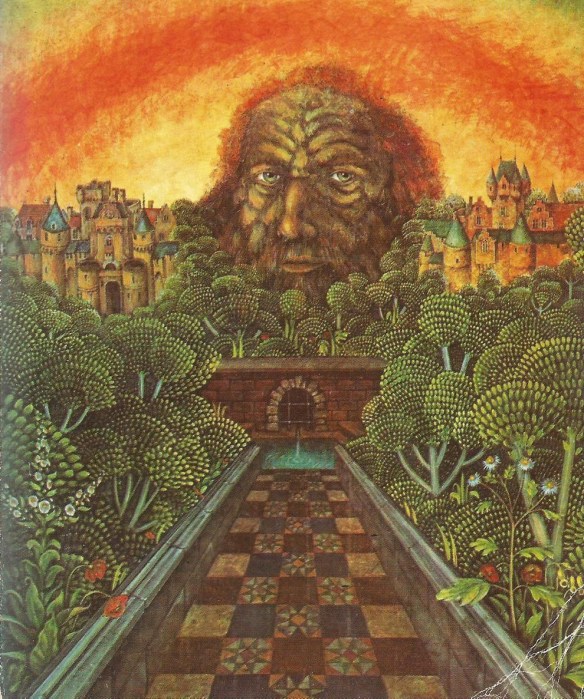

the 1983 Pan Books edition of THS.

THEY HAVE PULLED DOWN DEEP HEAVEN ON THEIR HEADS

Overview Question

This is the first of three chapters (along with Chapters 15 and 16) which clarify in one way or another who Merlin is, and what is his special role in the spiritual battle between St. Anne’s and Belbury. Chapter 15 will show how Merlin is equipped by the heavenly powers to undertake the battle. And Chapter 16 will show the destructive results for Belbury of Merlin’s engagement, like live video of an ongoing battle. In this chapter, however, we discover why God has chosen to use Merlin in the first place. Why doesn’t God just send down the heavenly powers themselves to destroy Belbury? Why wait for a man of ancient Logres and work through him?

This aspect of God’s strategy is announced most clearly in Part 5 of the chapter when Ransom explains to Merlin why God will not break the “Seventh Law” by allowing the planetary powers to work directly on the earth. As Ransom explains, “They will work only through man.” And then he goes on to explain why Merlin is precisely the sort of man that God needs for the job. One who is a Christian and committed to the ancient “natural” order of creation, yet also one who is a penitent and knows the ways of sinful man.

There is much in Ransom’s longer explanation that is simply part of Lewis’s fairytale (for example, his travels in space, and Merlin’s travel through time, as we saw in Chapter 9). These do not require a literal or concrete interpretation. But the principle of the Seventh Law, of God’s choosing to work only through a human agent, is another matter. Overview Question:

Given what you have already learned about the traditional worldview and its understanding of human nature (for example in the portrayal of Mark’s struggle with his own vanity until he finally calls out to God for help) why would God refuse to produce a spiritual victory by divine fiat rather than requiring the obedient response and practiced discipline of faithful human beings who turn to him for help? Why won’t God break the Seventh Law?

Deeper-Dive Questions

1. In Parts 1 and 3, Merlin and Ransom and the people of St. Anne’s must “vet” each other as to their respective bona fides—that is, they must test and prove to each other their allegiance to the right side. They do this by asking and answering questions that ferret out the principles upon which each of them takes their stand. In this way, Merlin discovers that Ransom is in fact the Pendragon, the heir of King Arthur and the realm of Logres; and Ransom discovers that Merlin is a Christian who affirms the gifts and disciplines of faithful marriage as well as the biblical tradition of God’s creation and providence. Similarly, the search party (upon their return and surprise at finding Ransom and Merlin together) are finally convinced of Merlin’s good faith when the Director vouches for his loyalty to the Christian essence of Logres (which Dr. Dimble had long wondered about and hoped for).

In this light, our own question about the bond between Merlin and St. Anne’s must be equally probing: To what group or tradition do these principles (King Arthur, Logres, the Bible, Christianity, faithful marriage, etc.) correspond in the cultural and spiritual battles that we face and fight today, and that Lewis faced and fought in post-war England? What is it that Merlin stands for (along with the people of St. Anne’s) in the battle against the dark spiritual forces of the NICE?

2. Part 2 of Chapter 13 gives us another peek into the troubled lifeworld of those at Belbury who hold the modern worldview. While discussing their strategy for working with the tramp (their false “Merlin”) Wither and Frost are drawn into a set of sniping and threatening remarks toward each other. What is it about the modern worldview (with its conception of the individual, the “freedom” of the individual, and “universal” reason) that seems to provide the perfect seedbed for this kind of combative and divisive social atmosphere?

3. In Part 4, Dr. and Mrs. Dimble discuss the effect of Merlin on the people at St. Anne’s and speculate about how Merlin’s influence will affect the whole course of their battle with the NICE. Dr. Dimble notes Merlin’s ancient and intimate connection with nature in contrast to the modern view of nature as a machine, and even more in antipathy toward Belbury’s desire to change, alter, and work against nature (the anti-nature posture that we have noted before). And then Dimble observes how everything in the cultural and political atmosphere seems to be polarizing, “coming to a point,” as he puts it: “Good is always getting better and bad is always getting worse.” Then Mrs. Dimble sees how this is like the biblical portrayal of judgement when the “wheat is separated from the chaff.” Where in the polarizing events of our own time do you see such a separation between good and evil taking place, and what other biblical grounds can you suggest for advocating this view of our own cultural, political, and spiritual battles, especially right now as the midterm elections pressure everyone to make the “terrible choice” (Mrs. Dimble’s reference to Browning).

4. In Part 5, Ransom defines for Merlin what will be the necessary tools and methods by which the battle with the dark eldil can be won, but only if Merlin will submit to the part he has to play. At the same time, Ransom also clearly and forcefully rejects certain other tools and methods that Merlin finds more congenial to his tastes and confidence. Thus, Ransom rejects Merlin’s acquaintance with ancient natural magic and remedies because they are no longer “lawful,” and because they are merely earthly in scope. Something more powerful is needed. Also, Ransom rejects the resort to national, global, or ecclesial authorities because they are already tainted with the same evil infection and anyway, they also do not possess the necessary kind of power to defeat the dark powers.

Instead, according to Ransom, what is needed is a human being, a Christian and a penitent, who is willing to be invaded by the powers of heaven in order not only to withstand the evil influences of the dark eldil, but also to draw them out into the light where they will have to face the ultimate consequences of their own choices. What is needed is a person who is willing to have his own heart changed in this way so he can be used by heaven in the wider world to expose and defeat the dark powers, and to help establish under God’s rule the good community of the restored creation. How does this definition of Merlin’s role expand and fill in the principles we have already noted regarding the tradition of Arthur and Logres, the Bible and Christian marriage? Is there a political, spiritual, and cultural tradition in our own time (as well as in Lewis’s time) that embraces these same basic principles and commitments? If so, what is it? And what would it take to recover it today?