THE PENDRAGON

Overview Question

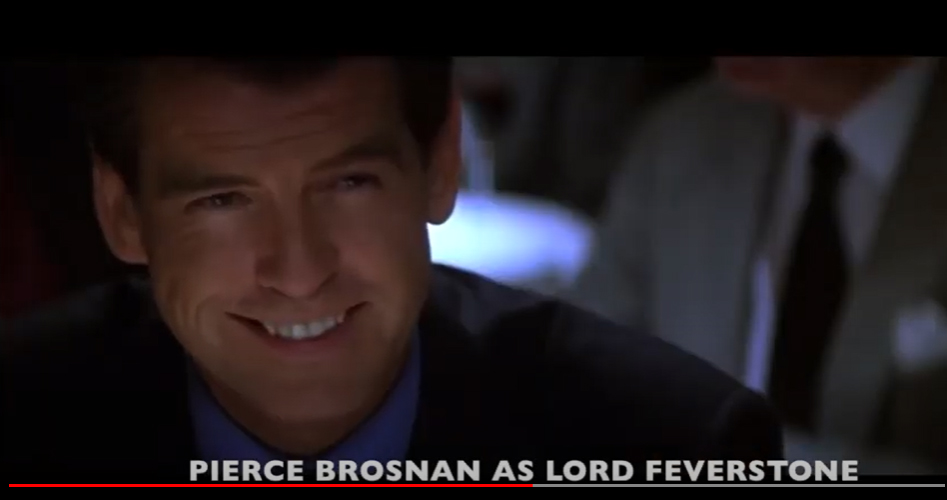

From the opening sentence of THS, and scattered throughout the chapters, we encounter various clues concerning Jane’s ideas about marriage and sexuality, and these are always unresolved ideas. In the opening paragraphs of the story, for example, we find Jane struggling with her ideas about romantic love and with the reality of her marriage to Mark in comparison to the high ideals of the marriage rite in the Church of England. Then, when Jane first goes to St. Anne’s, she is caught up in a train of thought about sex and gardens, Freud and female beauty that leaves her rattled and ill-at-ease until, embarrassed and trying to compose herself, she pulls herself together to meet the people she has come to see. And then, clearly, when she finally meets Ransom, the Director of St. Anne’s (aka the Pendragon) she goes into a bewildering spate of emotional reactions that includes overpowering attraction to him as an almost mythical figure of masculinity and, at the same time, a strange disloyalty and indifference to her own husband, Mark. And all of this happens to Jane, of all people–a woman who wants, above all, to be (or at least to appear to be) in full rational control of her own thoughts and passions, and to write a cutting-edge dissertation on John Donne’s “triumphant vindication of the body.” Overview Question:

Given what you know already about Jane’s worldview and her personal self-image as an independent, rational, egalitarian woman, how would you explain this meltdown in her composure and self-control when she first meets the Pendragon?

Of course, the wild career of Jane’s story in this chapter doesn’t end with her interview. Ransom tries to help her by introducing her to the role of faith, faithfulness, obedience, and submission in religion and in marriage. And when she leaves, she finds that she is indeed beginning to see her own beauty in a very new, though still confused and conflicted, light. And then she is subjected to physical and sexual abuse by Fairy Hardcastle upon her return to Edgestow, before deciding to go straight back to St. Anne’s to seek recovery. The whole chapter, then, pulls back the curtain on the deep conflict in Jane between her preferred outward self-image, on the one hand, and the inward terrain of a still very disordered and confused though seeking self, on the other. And so, again, how would you explain this? Keep in mind the two worldviews (modern and traditional) and the two lifeworlds, including both the principles and the practices of each, that either prepare the soul or leave it unprepared for various kinds of challenges.

DEEPER-DIVE QUESTIONS

1. “Pendragon” is, of course, the traditional name in the Arthurian legend for the line of kings that descend from King Arthur himself. Jane has not really wanted to meet with this man, this “Director,” also called Ransom and the “Fisher-King.” But her encounter with Prof. Frost in Edgestow, after having seen him first in a troubled dream, has jolted awake her sense of danger. Then, when she does meet with Ransom, she is “undone,” as the narrator tells us in Part 1; and she becomes distracted, giddy, “all power of resistance . . . drained away.” Given what you know about Jane so far (her feminism, her desire for rational control, her distaste for vulnerability, her modern worldview) what do you think could explain this sudden meltdown?

2. In a way, Jane’s conversation with the Director goes from bad to worse. She finds herself attracted to him. She argues with him about the nature of her marriage to Mark and the role of equality in marriage. And then when he tries to explain to her the connection between obedience to God and love for one’s spouse in marriage, she seems to lose herself in a kind of seductive fantasy about Ransom himself, until Ransom tells her to “Stop it.” He then goes on to try to help her understand the role of “obedience” (humility, faithfulness, submission) in romantic or erotic love (Part 2). What does this conversation suggest about the relevance and value of Ransom’s traditional worldview for Jane?

3. When Jane leaves the Director in Part 3, the narrator tells us that she is divided within her own mind and emotions between four different “Janes.” Identify these, and try to explain what each one means in terms of the spiritual journey that Jane now finds herself embarked upon.

4. When she arrives back in Edgestow, Jane is caught up in a riot that has been ginned up by the activists from Belbury. Jane is then taken prisoner for interrogation by Fairy Hardcastle, and subjected to painful physical and sexual abuse. In the turmoil of the riot, Jane manages to escape and to ask some strangers to take her “home” to St, Anne’s. After this day of wild extremes and emotions—both of deeper good and of really horrible evil—how would you assess Jane’s decision to regard St. Anne’s as her home, rather than her own flat in Edgestow?