In his letters to the Christians in Galatia and in Rome, the Apostle Paul explained with great energy why the coming of the Messiah into the world, “to give himself for our sins and to deliver us from the present evil age” (Galatians 1:4), leaves no room for ethnic divisions, jealousy, or strife within the single family of God’s people. Indeed, according to Paul, God’s purpose from the beginning, as in the covenant promise to Abraham, has been to make one family of his people across all national (that is, ethnic) and cultural boundaries. Jesus confirmed this promise in his “great commission” (Matthew 28:18-20). And so, Paul declares with great boldness:

“For you are all children of God, through faith, in the Messiah, Jesus. You see, every one of you who has been baptized into the Messiah has put on the Messiah. There is no longer Jew or Greek; there is no longer slave or free; there is no ‘male and female’; you are all one in the Messiah, Jesus. And if you belong to the Messiah, you are Abraham’s family. You stand to inherit the promise.” (Galatians 3:26-28)

This was radical stuff in the strictly stratified culture of ancient Rome. It is radical stuff today. The church so aligned with its Lord (then and now), like Jesus at the beginning of his ministry, rejects Satan’s temptation to seek power by exploiting the nations (the ethne, Matthew 4:8-11). And like a city set on a hill, the church thereby demonstrates the power of his resurrection, the beginning of the new creation, his victory at the cross over the fallen powers, including the power of race itself where this has become disordered and abused. But what then does it look like as we live this life of new creation in our risen Lord and in his Spirit–where he is putting everything back in order, where there is neither Jew nor Greek, where race itself literally does not divide us?

In our current culture wars in America today, there are primarily two opinions about how to deal with issues of race and ethnicity. In order to avoid using merely partisan tags and labels, we may think of these in terms of two major leaders who speak for these two views, Robert Woodson and Ibram Kendi.[i] In Kendi’s view, using the ideas of Critical Race Theory (CRT), the topic of race itself must be the primary focus for improving race relations. We must, therefore, divide people into groups according to their skin color, and judge them as oppressors (if white) or as victims (if black or, perhaps, people of color). No room here for differences among individuals based on traits of character, moral choice, or personal behavior. Then, we should proceed by creating government programs that favor the black victims and restrict or penalize the white oppressors.

In other words, according to Kendi’s view, we must follow a strategy that is exactly opposite of Paul’s view, as well as being opposed to the practices of Martin Luther King, Jr., who called Americans to judge one another “not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Kendi, by contrast, regards the principle of “colorblindness” itself as a pillar of racism because it does not force the collective pre-judgement (what I would call the racial profiling!) demanded by CRT and the concept of “systemic racism.”

From the other side, Robert Woodson warns America that Kendi’s approach only creates division, envy, animosity, victim mentality, and lust for power. Indeed, Woodson regards CRT as a form of racism more insidious than the old-fashioned type of the KKK which was obvious on the face of it. Moreover, by focusing on race as an end in itself (as the CRT, DEI, ESG, and other government and corporate programs are now doing), we only make matters worse for the very people we say we are trying to help. The “race hustle,” as Woodson calls it, has a terrible history of failure. In the fifty years or so since the welfare state was created by LBJ’s “Great Society” programs, some 42 trillion dollars have been spent. Seventy percent of this went to operating costs for the government’s own overhead, not to recipients. And the inner cities have only gotten worse in every area of basic measurement (single-parent families, illegitimate birth rates [now 70%, up from 20% in the mid 1960s], educational outcomes, low income, neighborhood blight, violence, etc.).

By contrast, says Woodson, we should follow the guidance of Scripture, and focus instead on three basic things: 1. the grace of God extended to all people, all of whom are sinful, 2. the gifts and purpose that God has for every individual person, and 3. the goal of unity in a colorblind congregation, community, and society. Thus, Woodson champions leaders of every color, especially in the black community, who have become mentors for the people in their own neighborhoods. Such local, grass roots leaders demonstrate how to be responsible for one’s own life, and to succeed with discipline and dignity, even when there are still others around (including the CRT group and the white supremacists, strange bedfellows!) who insist on pre-judging people by the color of their skin. He calls these mentoring exemplars “Josephs,” for the role they play in leading the whole country toward healing, wholeness, and “a more perfect union.” As a result, the Woodson Center, in contrast to the welfare state, has a long history of major and sometimes miraculous success participating in the transformation of individuals, neighborhoods, and communities.[ii]

The difference between these two visions could not be more pronounced.[iii] One is highly idealistic, self-righteous, and brooks no dissent from its agenda, requiring a kind of “group think” from everyone, and ready to cancel or censor those who don’t toe the line. The other is realistic, recognizing that people are not perfect, that we are in fact sinful; but that we make progress by taking measured steps grounded in faith and moral tradition as we make our way toward “a more perfect union.” And only one of these visions is consistent with Paul’s vision of how the incarnate, crucified, and risen King, Jesus the Messiah, is restoring his people, even now, by the power of his Spirit, putting everything back into the proper order of creation, and building the new creation that is yet to be fulfilled.

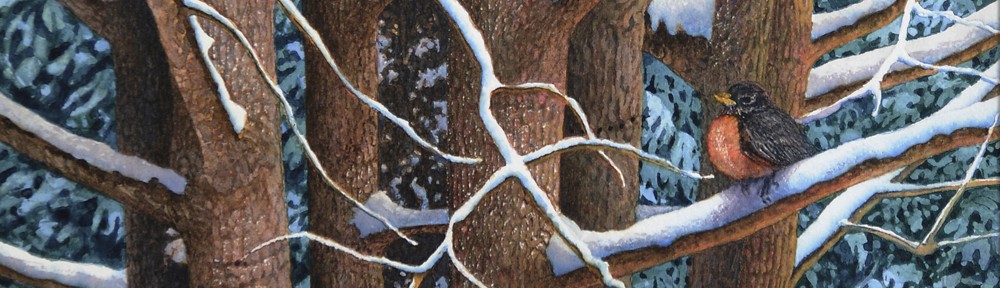

The song that Deb and I are sharing this week, Some Children See Him, also follows Paul’s vision of the Messiah’s single family–making our way together in him on the road of new creation. Each verse of the song portrays children who imagine the baby Jesus as a member of their own ethnic group (though of course, historically, Jesus was not a member of any of the groups mentioned). Each verse shows, moreover, how our Lord’s life, his love, and his power, nonetheless, reach children (and people) in every group. And then, still ringing with Paul’s vision, the emphasis on groups stops, and we stand individually before Christ himself. In the light of his holy Light, we affirm our ethnic and racial heritages, to be sure; but we do not let them become an idol, separating us from him or from each other. Rather, we hear his own invitation through the music of jazz musician, Alfred Burt, and the words of Wihla Hutson:

O lay aside each earthly thing.

And with thy heart as offering,

Come worship thou the infant King.

Tis love that’s born tonight.[iv]

[i] Robert Woodson is a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement, who pulled away from that movement when he saw it turning into what he came to call the “race hustle” of the welfare state. He saw black and white elites growing wealthy by creating expensive programs that signaled their own virtue but did little to change conditions for the people they were supposed to help. In this assessment, Woodson is the protégé of Thomas Sowell. For further reading, see Robert Woodson, The Triumphs of Joseph: How Todays Community Healers Are Reviving Our Streets and Neighborhoods. Ibram Kendi is one of the more prominent academic teachers of contemporary neo-Marxist ideas about race, based on the concept of “systemic racism” and the methods of Critical Race Theory. For further reading, see Ibram Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist, and Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

[ii] Woodson’s vision, following Paul and the Bible, does not ignore or demean our different ethnic heritages—the things that make us ethnically and culturally different from each other: for example, food, fashion, music, and even many of the elements that shape the way we worship God. But neither does he see why different groups should be forced by an academic or a government program to adopt the same cultural style, customs, congregation, or neighborhood. Rather, Woodson affirms the approach of Paul in Romans 14. We should leave room for our cultural differences (Paul’s word is adiaphora, that is, non-essentials). We should in fact honor these in our own and in each other’s lives. But we don’t have to force everyone into a single style. Thus, we may be different in our ethnic heritages without shame or guilt, and also united in our love for the living God who knows each of us from our mother’s womb and has a unique plan for each of us in his new creation.

[iii] The mention of two visions invites a further reference to the work of Thomas Sowell. Sowell has done as much as anyone on the planet to document with hard empirical evidence the ideas and actual results of the two visions we are examining. See Thomas Sowell, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles, and The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Public Policy.

[iv] I take Hutson’s reference to “earthly things” here to mean precisely the ethnic and racial differences (adiaphora) that distinguish us culturally from one another in comparison to the unity that we have in Christ our Lord as fellow sinners made alive in the Spirit and making our way together with the single family of God toward the fulfillment of the new creation.