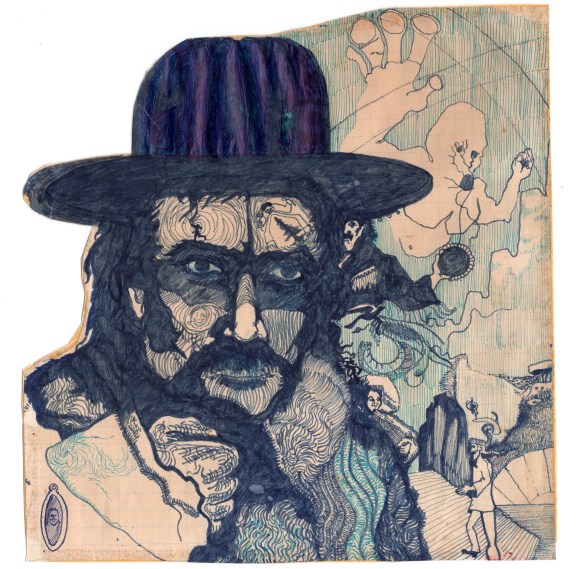

A picture drawn in 1968 of my older brother Jerry, which also reflects how I saw myself, especially after our dreams for the “Summer of Love” began to crumble and fall apart.

After returning to Fort Worth from Haight-Ashbury in the summer of 1968, I was in an emotional and mental crisis. I had seen, and partially registered, some of the inconsistencies, some of the dysfunction, and the short-sightedness of the youth revolution in San Francisco at one of its central meccas; and yet I was also still alienated from my parents and their version of culture, religion, and life as well. They saw that I was suicidal for a while and, I am sure, prayed for me a lot. Yet, by the time the fall semester of what would be my first year in college rolled around, I had decided to make another stab at posing for the revolution with my old friends. I tried to register for the Vietnam draft as a conscientious objector in downtown Fort Worth; but was rejected and put into the normal lottery with everyone else, number 165. I moved into an apartment on the campus of the University of Texas at Arlington with a couple of friends, and our place became a hangout for a group of about twenty like-minded comrades. We formed a rock band, took drugs, played concerts at area colleges, preached and practiced “free love,” and looked for ways to make our mark as campus revolutionaries.

At the same time, I was constantly troubled by what, at an increasingly conscious level, I recognized as the weakness, ignorance, and arrogance of my and my friends’ positions. And I continued to read in secret other sources that put me in contact with a Christian view of things. Most significant in this regard was the Gospel of John, which gave me a window into the life of a person whose faithfulness was unlike anything or anyone else I knew, both scary and somehow reassuring. But I was in a state of cognitive dissonance, still trying to keep up appearances as a heroic young revolutionary. There was still a good deal of deconstruction left to do in my life, much more than I could have imagined.

As part of our revolutionary effort, I and several others in our group joined and helped to start the UTA chapter of the “Students for a Democratic Society” (SDS). This was a counterpart at that time to the kind of political philosophy one hears of today (in 2020) from people like A.O.C., Black Lives Matter, and others on the Left. Our group organized and participated in various public demonstrations, joining our voices with what were, in retrospect, perhaps sometimes “righteous” and sometimes not so righteous causes. We organized, for example, a “Pro Castro Rally” in one of Arlington’s public parks. We put up posters and sent out brochures. Bernie Sanders would have fit right in. On the day of the rally, as our speakers tried to hail the virtues of Castro and communist Cuba through a public address system, we were surprised to find that a large group of anti-Castro Cuban refugees (who had lost their homes, sometimes their families, and their country to Castro’s regime) showed up to shout and stare us down. I think we thought the crowd that day would be mostly other college kids out to demonstrate their political consciousness (like many of the “woke” today).

As I stood in the front line on our side, I looked across the gap between the two groups of demonstrators and saw my father looking back at me. He was standing in the second row of the counter-protestors, but he was not shouting. His face showed concern. When the rally was over, my friends and I went back to our apartment, proud of our demonstration and fairly sure of our righteousness though, truth be told, I could not at that time have told you anything beyond what our SDS speaker had asserted about Castro’s ideas, or what Castro had actually done on the island of Cuba. And I’m pretty sure the same could be said for most, if not all, of my friends. Being ill-informed and dogmatic is a heady, but a dangerous, cocktail. Dad never spoke to me about that day, or asked me any questions about it, though he had majored in International Law at UT Austin in his college days, and had also made a special study of Cuba, as I later learned.

I suppose someone reading this might interject, “Well, you were just being a normal adolescent, rebelling, striking out to find your own identity, etc.” And that would be true as far as it goes. But, remember, like those who are demonstrating and sometimes rioting today, we were taking positions on pivotal political issues, and we were beginning to vote, and to shape the future of this country. Indeed, the future we shaped then is in many ways fully visible in the present we are all living now. Yet, very often we were motivated (as seems also to be the case today) by little more than our hormones and a desire to appear bold and brave at the demonstration.

I might have continued to live, party, demonstrate, and accept the superficiality of our political and historical analyses at that time for who knows how long, had my own personal life not also been caught up in the inconsistency and self-indulgence of the scene. My friends and I saw, or at least we admitted, no contradiction between our high moral claims on selected social issues while, at the same time, rejecting any moral claims that might be placed upon our personal and sexual behavior. But in this, I reluctantly came to believe, we didn’t take account of the ways of the human heart, how we as human beings are made to live and love, and the need for faithfulness and commitment in any love that is worth having.

This finally came home to me when a young woman I was with at the time became pregnant, and we decided to have an abortion. I (and I think she) didn’t want to be tied down right then to a family, and I was already on the verge of taking up with someone else. But I also knew, somewhere in my gasping conscience, that there was something deeply wrong in all of this. Though my friends had no problem with it, it became a torment to me. I was reading The Problem of Pain, and realizing that much of our pain we bring upon ourselves, a lesson I had “learned” before. And I saw Jesus in the Gospel saying to the woman caught in adultery, “Neither do I condemn you. Go and sin no more.”

I wish I could say that I saw the light and decided to do the right thing, to marry this young woman, and to bring that child into the world. But I did not. She had the abortion, and I moved along to another relationship, which also later foundered. But in my secret reading of the Gospels, and in the beginning rudiments of prayer, I began to see myself for what I was. What I had become. Yet also to see a picture, in the face of Jesus the King, of the kind of person I might become. And, slowly, something began to turn inside of me. I finally came to a place with my “revolutionary” friends where, sitting together in a room of an evening, and listening to one of our more vocal leaders tell of how we were going to change the world, I objected. To everyone’s surprise, including mine, I found myself saying, “Do you really think that we are going to change anything?” Everyone’s jaws dropped open. But no one said anything.

Over the next two years, I continued to read, to think, to pray, to begin to apply myself to study, and gradually to separate from my old crowd as I found other people like myself who were trying to figure out what it would look like to care about social and political issues and yet, also, to be a Christian, a person of faith and of faithful relationships. And I continued to write songs, one of which was the story of the SLO. CO. JAIL, only now told with a further layer of deconstruction in place, and at least a hint of what reconstruction might look like. I realized even then, looking back on my journey since Haight-Ashbury, that I had gotten out of the SLO. CO. JAIL a long time ago; but I was still in jail in my heart and life.

THE SLO CO JAIL

Summer of 1968, San Luis Obispo County,

Peanut butter and jelly, standing on the street, waiting for him.

We stepped into a chapel and found the perfect gift

To set his mind on freedom.

It was Jesus, in a blood-red ruby stone.*

But the SLO CO JAIL, it’s a lonely place.

O, the men inside have such a lonely face.

Driving down the coast road, staring at the ocean.

And it’s so beautiful with the sun upon its motion.

We were heading down to Mexico, gonna make our fortune.

But we’re so fortunate we never made it.

And the SLO CO JAIL, it’s a lonely place.

O, the men inside have such a lonely face.

What are those cagey shadows hanging on my wall?

No, I don’t think I’ve been here before.

And wild geese flying toward heaven, and Jesus in a blood-red ruby stone,

Cannot free this heart of mine.

But just as iron bars do not a prison make, neither can blue skies give freedom.

What are those cagey shadows hanging round my heart?

And wild geese flying toward heaven could only remind me

Of my desire for freedom.

But Jesus’s blood, dripping on the stones, set me free to soar.

And the SLO. CO. JAIL, it’s a lonely place.

O, the men inside, have such a lonely face.

And the SLO. CO. WORLD would be a lonely place

Had the Lion himself never shown his face.

*The reference to “Jesus, in a blood-red ruby stone” is about a trinket that one of our group bought in a small Catholic chapel to give to Jerry while we were waiting on the street in San Luis Obispo for him to be released. It appears in my 1968 drawing in the lower left corner.

In Part 3 of this reflection, I will take back up what it means to say that, unlike the trinket for Jerry, “Jesus’ blood dripping on the stones set me free to soar.” For that is finally what this reflection is all about. How the Gospel of Jesus’ death and resurrection has the power not only to deconstruct us from the false narratives, and the superficial posturing to which we become bound, but also to reconstruct us as the unique individuals that each of us is in the image of our Creator, who made and loves each one of us. Though that process may for some of us take a considerable amount of time.