VENUS COMES TO ST. ANNE’S

Overview Question

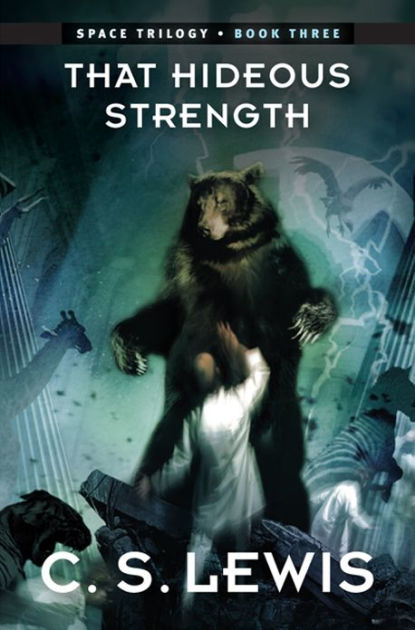

In this final chapter, Lewis brings a few things to a sort of penultimate completion, for example the roles of Merlin and of Dr. Ransom. At the same time, he leaves us with a set of characters and questions that, rightly engaged, pull us back into the world of our own lives (our families, our congregations, our communities, and nation) to ponder our own course on the road ahead.

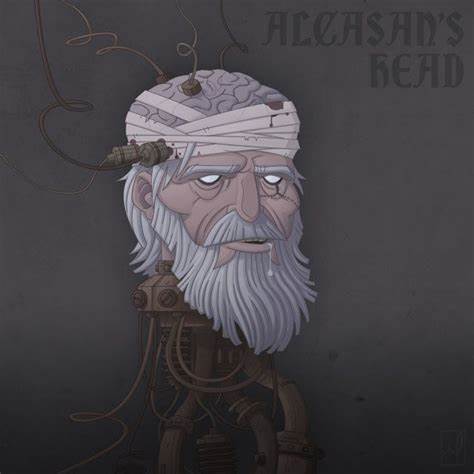

We have seen in earlier chapters how Ransom and Merlin, and the members of the community at St. Anne’s, have so far responded to the spiritual battle with Belbury and Edgestow in which they have been engaged. Now, in the final chapter we overhear, so to speak, their conversations about the ongoing battle that they have yet to face, and the parameters within which they must make their battle plans for the future. These parameters include hints about the ongoing “conversions” of Mark and Jane and the others at St. Anne’s (Parts 1 and 2); but also some more explicit statements about the nature of Logres, going forward, when the community at St. Anne’s must be prepared to meet again and to fight back against “other Edgestows” (Parts 4 and 5) under the same kind of distorted leadership as before (e.g., Curry, the well-informed man in the train of Part 5). This brings us to our final Overview Question:

Taking the story of THS as a whole, especially the sense of future direction that arises in the final chapter, what would you say are the key principles—both at St. Anne’s and for us—that define the goal of their/our lives, and the signs that they/we are in fact making progress toward this goal?

DEEPER-DIVE QUESTIONS

1. In Part 1, after the debacle of the banquet, Mark is making his way to St. Anne’s on the Hill to find Jane and to give her “her freedom.” What are the signs that the conversion already begun in him is really taking root and expanding into various parts of his personality and the habitual way of life (the lifeworld) that he had formerly considered so important? What does this portend for Mark’s future, his marriage, and his potential for a different role in society?

2. In Part 2, Jane is with the other women of St. Anne’s trying on beautiful dresses in preparation for a great meal that the men of St. Anne’s are preparing. What are the signs in Jane’s thoughts and attitudes that the conversion already begun in her is also expanding into the wider regions of her personality and her former habitual way of seeing herself and trying to present herself to others? What does this portend for Jane’s future, her marriage, and her potential for a different role in society?

3. In Part 3, Lord Feverstone comes to his end swallowed up in an earth quake at Edgestow. He dies in a manner reminiscent of the sons of Korah in Numbers 16, and for the same reason: He has placed his own fame and fortune above everything else in life, and so he vanishes into nothing. At the same time, Part 3 gives us the last mention of Merlin who rides away on a horse yet, as Jane has seen earlier in one of her dreams, he has also been like a pillar of light used up completely in God’s good work of deliverance at Belbury. What do these very different “ends” tell us about the worldviews and lifeworlds of Merlin and Feverstone?

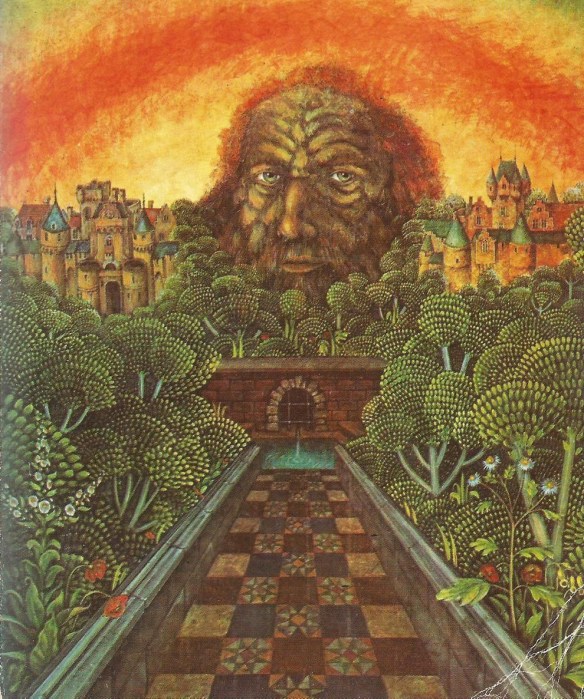

4. Part 4 begins with Camilla’s question, “Why Logres, Sir?” which she asks of Ransom; though it is Dr. Dimble and Grace Ironwood who do most of the answering. In their answers, they talk about the importance in Logres (the ancient realm of King Arthur, which we commented on at some length already in Chapter 13) of a certain understanding of “Nature” (what I would call creatio continua), and of the tradition of faith and freedom that “haunts” English history all the way back to Arthur (and before), and of how this tradition must often be pursued in the most mundane ways, as they have in fact been pursuing it steadily at St. Anne’s. Working with your earlier answers in Chapter 13 and elsewhere, how would you define the meaning and significance of Logres, both in the story and in the present world of American culture and politics which also reaches back into this history?

5. At the end of Part 4, there is also a discussion about the status of other countries in relation to Logres (this haunting of England) and about the seeming unfairness of the judgement of the people of Edgestow. What do the conversations about these two issues tell us about the traditional worldview, at least as C. S. Lewis understood it and recommended it through the characters in his story? What parallels can you find in Lewis’s other works to support your answer?

6. Part 5 is all about the future prospects of Curry, the Sub-Warden (“Dean”) of Bracton College. This is the Curry who in Chapter 1 manipulated the faculty of Bracton to sell Bragdon Wood to the NICE with a view to padding the purse of the college as well as his own career, and without even considering the moral or spiritual dangers. In Part 5, Curry discovers a way to turn the tragedy of the destruction of Edgestow and the college into a “providential” turn of affairs for himself. Why is it significant in the story that Lewis portrays Curry as the kind of man that people will see as empathetic and wise, though in reality Curry is only thinking of the future (and even of God’s providence) in terms of his own fame.

7. The final part of the chapter, Part 6, is focused on the theme from which the chapter takes its title: “Venus Comes to St. Anne’s.” In addition to all of the echoes of Genesis 1 among the animals (“be fruitful and multiply”), why does it make perfect sense, given where the story of THS begins (with Jane contemplating the emptiness of her marriage) that the story would end in a chapter with this title? That is, with Jane and Mark Studdock coming together as husband and wife in a way they have never before been able to do? What are the chief virtues that seem to characterize this new potential for marital union? And how will this practice of faithful marriage strengthen their ability to promote the cause of Logres in England going forward?